|

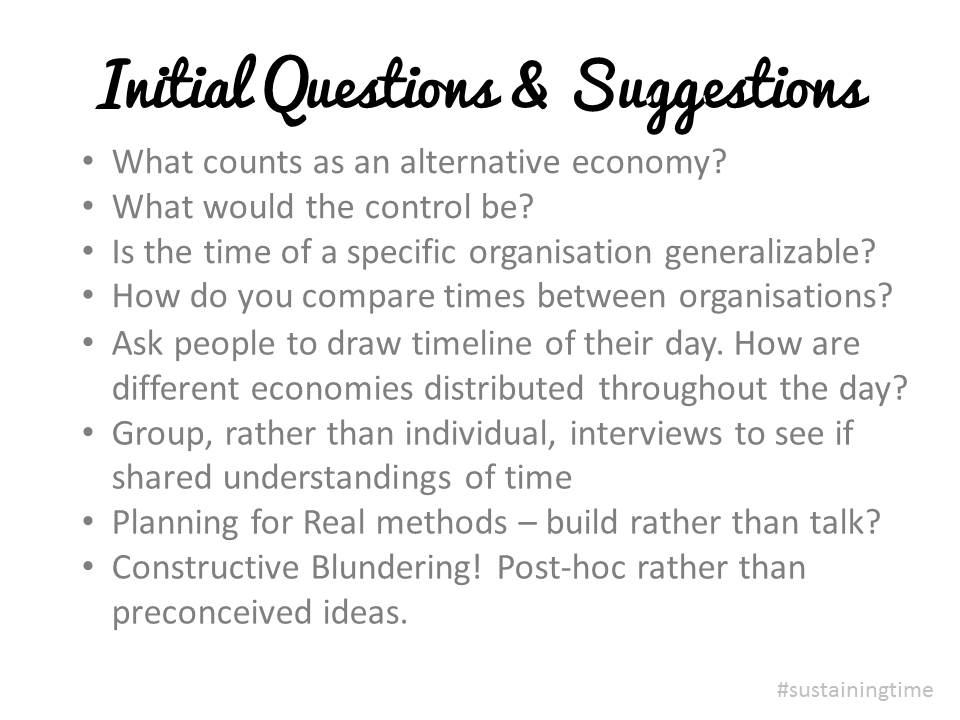

Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy? A key question for us since we first started thinking about this project, was not only what is the time of sustainable economies, but how we might find it. How on earth do you actually go about researching people's perceptions of time? As anthropologist Kevin Birth writes eloquently in his paper Finding Time: Studying the Concepts of Time Used in Daily Life: Cultural conceptions of time do not lie by the side of the road waiting for an ethnographer to wander by and pick them up. Indeed, the idea of the naïve fieldworker walking up to some beleaguered informant and asking, “What are your cultural ideas of time?” is amusing in its absurdity. There is something about time that makes it seem extremely important to understanding how people live, yet it seems an intangible concept. It seemed to us that the project provided a great chance to address a series of interesting methodological questions. Work that has come out of the AHRC Connected Communities theme, for example, has raised a number of questions about the ability of established research methods to do justice to the dynamic nature of communities (see particularly McLeod & Thomson 2009; Law 2004; Abbott 2001). They suggest that need to understand communities as being in time, (or even as producers of time), just as much as the more usual focus on communities and space, territory, locality etc. We were also intrigued by the development of methods for researching experiences of space as changing and dynamic, which have been coming out of the mobilities research paradigm (Buscher, Urry, Witchger 2011). What methods might researchers use to study the way time itself can also be changing and dynamic, rather than simply assuming that time provides a taken-for-granted background to everyday life? Since the remit of this project was, above all, to be exploratory, we created a variety of opportunities for us to reflect on methods as the project progressed. We asked for advice from our Project Partners and Advisers and I've summarised their suggestions in the slide below: In some ways the approaches we have been using are perhaps on the more conservative side, in that we are focusing primarily on archival research, participant observation and open-ended focus group interviews. Even so we've been finding that attempting to use these methods to research the slippery subject of time has ended up working back on the methods themselves. You can read about Alex's experiences in the archives here and here, for example, and we'll be adding further reflections as we go along.

But given that we were also aware that there are a wide variety of other methods that have been developed, we were excited to be able to include a Methods Festival for Studying Perceptions of Time, which took place on the 26th of June 2013. Organised by Jen Southern, this event explored the potential of arts, design and technology practices for researching shifting temporal paradigms, as well as a number of different ways that social science methods have been put to use in studying time. The talks from this event are now online and can be accessed here. References Abbott, A. (2001). Time Matters: On Theory and Method. Chicago, University of Chicago Press. Birth, K. (2004). "Finding Time: Studying the Concepts of Time Used in Daily life." Field Methods 16(1): 70-84. Bryson, V. (2008). "Time-Use Studies: a potentially feminist tool?" International Journal of Feminist Politics 10(2): 135-153. Büscher, M., J. Urry, et al., Eds. (2010). Mobile Methods. Abingdon, Routledge. Law, J. (2009). After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. Abingdon, Routledge. McLeod, J. and R. Thomson (2009). Researching Social Change: Qualitative Approaches. London, SAGE. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed