|

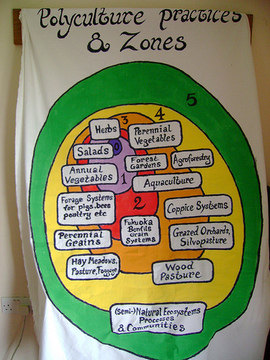

Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy?  London Permaculture (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) London Permaculture (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) Another organisation I’ve visited recently is Lammas, a planned low-impact eco-village in North Pembrokeshire. I attended the recent Low Impact Experience week run by Hoppi Wimbush and also interviewed some of the villagers and volunteers. There are lots of notes and interview transcripts to go through, but I wanted to share some initial observations about possible links between permaculture and developing a more critical relationship to time. As Chris Warburton-Brown from the Permaculture Association has pointed out, “unlike other finite resources that are in short supply in post-industrial society, most of us in the environmental movement have not yet formulated much response to the shortage of time we often experience”. So one of the questions we wanted to look at in this research project is, if permaculture is a design system for working with finite resources in a sustainable way, how might it help us with our widespread feelings of time pressure? One really interesting issue that came up in conversations about time and permaculture while I was at Lammas related to the idea of zoning. In fact this issue arose as part of a discussion about how permaculture was more obviously about space than about time. That is, seeing permaculture as a way of designing space seemed most obvious and intuitive. Zoning, of course, provides a perfect example of this. This is the technique of locating plants, animals and other features based on how often you interact with them. So trees for coppicing would be planted further away than herbs which might be used daily in cooking. On the other hand, you could also argue that zoning is also a way of designing time. It minimises wasted time, for example, by ensuring that you don’t have to walk right to the back of your garden every time you want a sprig of mint. But more than that, zoning seems to involve judgements about which rhythms you need to be most aware of and which you can pay less attention to. I couldn't help thinking it would be really interesting to explore how these kinds of decisions are made. What kinds of conflicts arise in the process? What happens when a rhythm or cycle that you thought you didn’t need to be so aware of (and so placed further away) actually starts becoming more important? Does explicitly considering the differing cycles involved in your work processes (e.g. once a day for compost or once a decade for coppicing) create a more sophisticated and multi-layered sense of time? How might this kind of decision making process be used in daily life to manage the differing rhythms of work, family, volunteering, friends, leisure etc? I think it’s really intriguing to try to think of clocks as devices for zoning time. That is, they bring some rhythms closer to our daily attention while backgrounding others (see my paper on this [PDF]. My favourite example of this is the way that a clock can generally tell me whether I’m late for the bus, but not whether we are too late to mitigate climate change. One might say that in this case the bus seems to be included in Zone 1 (nearest to 'the house'), while the climate is in Zone 5 (in the ‘wilderness’). This is of course a real problem, so how might we zone time differently if we paid closer attention to permaculture ethics and principles when we designed our clocks? Another issue that we discussed was stacking, where a permaculture designer aims for multiple outputs from a single process or space. So rather than planting an area with only one crop, you layer it with useful ground-cover, shrubs and trees. Again, in a way this seems to be about a more complex approach to space, rather than industrial agriculture where one field = one crop. But might this also work as a method of more sustainable time management? I thought initially that this might mean trying to do multiple things at the same time, although this can often lead to the dreaded stress-inducing need to ‘multitask’. So perhaps it can be more about designing your work so that a single process provides multiple benefits at the same time? Here the more general aim of reducing the amount of labour required to grow food through attentive design (e.g. Fukuoka’s Do-Nothing Farming) is also important. Finally, in the organisations I’ve visited so far, the issue of how to negotiate the way time, money and value have been inter-weaved within capitalist systems is coming up as a central issue (see this previous post). Many people are reducing the time they spent in waged jobs in order to use this ‘free’ time to develop businesses based on non-capitalist models. The impact of opportunity costs, particularly loss of monetary income, are weighed up against increased meaningfulness of their work and knowing that they are contributing to developing more sustainable ways of life. Those making these decisions still have to deal with the weight of others’ expectations and sometimes their own conflicting feelings about their choices. It seemed that the permaculture approach to accepting reductions in outputs from a single source in order to have a net increase in benefits might be an interesting way of thinking through this dilemma. For example rather than maximising wheat production over all else as we see in monoculture farming, a permaculture farm might produce smaller amounts so that other useful crops can be enjoyed as well. In the case of those moving away from maximising income, there seems to be an effort to move towards a more diversified understanding of value creation, where time might sometimes ‘produce’ money, but might also be used to grow free local food, to build community, to enhance one’s skills or just to enjoy life more. Thus reducing the production of one 'crop' in order to enjoy others more. So these are just a few thoughts from the work so far. I’m sure some of them have already been explored in permaculture literatures and practises and so I'd be really grateful comments or recommendations. Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy?  Repair Cafe Brussels (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) Repair Cafe Brussels (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) As well as visiting a number of UK archives, we will also be developing a range of case studies. Over the course of the project I will be visiting organisations who are trying to develop alternative economic models. I’ll be exploring whether this then leads to using, or thinking about, time in different ways. I’ll be visiting about 9 or 10 organisations in total and will be sharing what comes up along the way here on the blog. I visited The Restart Project early last month, my first case study for Sustaining Time. Restart was started by Janet Gunter and Ugo Vallauri in 2012. Their mission is to help grow a more widespread culture of repair. They organise Restart Parties in London twice a month, where people can bring along their broken gadgets and work with the Restart repairers (or Restarters) to try and find a fix. These events encourage more people to think about repair as a possible option for their gadgets, to become better skilled and to also save repairable items from ended up as landfill. They are starting small, but Janet and Ugo have big ambitions for their project. The are creating a world map of similar projects and are hoping to scale up their approach to support a global network of Restarters. They also clearly see themselves as contributing to a different kind of economy - laying the groundwork for the future, which they believe will be much more geared towards maintenance and repair than about continuing to buy more new stuff (see here). Like most (if not all) of the organisations I’m visiting, time is not really an explicit issue in their work. However, weaved throughout their website are quite a few examples where they appear to be challenging dominant temporal paradigms around use and value. I'll be exploring these in a series of posts. The first example of is their interest in questioning the life cycle of electronic goods. Rather than a model where we buy, use and discard, they state that they are seeking to promote “positive behaviour change by encouraging and empowering people to use their electronics longer.” Initially I wondered whether this meant they were interested in supporting a shift to a circular economy rather than a linear one. Arguably this kind of economy would draw on a sense of time which connected up the past and the future, by paying more attention to how things were produced prior to use and what would happen to them afterwards. This idea of the circular economy is explicitly contrasted with a linear model by a range of organisations interested in waste reduction (see here and here). However, when I asked Janet and Ugo about whether they saw themselves and moving towards a more circular or cyclical sense of time in relation to gadgets and repair, they expressed strong reservations. The danger of thinking in terms of the cycle, seems to be that this encourages people to think first about recycling, rather than about the ways their gadgets could continue to be useful now and into the future. Part of the reason they chose Restart for their name, rather than something with recycle in the name for instance, was to pick up on the way that for many electronic items the first solution to a problem is to simply to turn it off and then on again. That is, as Ugo said you “restart it and give it a second life, which didn’t necessarily mean that it had to be taken apart”. For the Restart project, recycling should be an absolute last resort and instead the emphasis is on prolonging your relationship to the gadgets you own. Their critical intervention into the short disposable time of current consumerism is thus not to champion a seemingly more ‘natural’ circularity. At least not a small circle that would move straight from use to recycle. Rather a more sustainable time for electronics comes from expanding the length of time we use our gadgets and prolonging our relationships with them. Recognising the way we have come to perceive something as old or obsolete every couple of years, they challenge the temporal boundaries that constrict ‘usefulness’ to such a short period. For example when people ask them what smartphone they should buy, their answer is “The one you already have. Keep it”. For Ugo and Janet, their ethic of time relates well with the New Materialism proposed by Andrew Simms and Ruth Potts. The second statement in their manifesto, for example, is “Wherever practical and possible develop lasting relationships with things by having and making nothing that is designed to last less than 10 years” (2012, 27 [PDF]). What is really interesting about this is that Restart seem to be suggesting that a particular kind of linear time, which is often thought to be the bane of sustainability, might actually be more suitable than a straightforward shift to a cyclical framework.  I've finished the write up for our second workshop in the In Conversation with...:Co-design with more than human communities project. See here for our approach to trying out Participatory Action Research with bees. Originally published on the More-than-Human Participatory Research blog, an AHRC funded project exploring the possibility of extending participatory research techniques to non-humans.  Part of being attentive to the possibilities of more-than-human participation in research is watching out for the ways that the traditional division between human agents and non-human subjects gets complicated in real life practices. I had been keeping this in mind throughout our In Conversation with Bees workshop, since we had quite a few discussions about different methods of beekeeping (e.g. frame versus natural) and how this might be interfering with bees preferred behaviours. But scattered throughout the two days were also a wide range of examples of how bees also shape the behaviour of the humans who keep them. Interacting with bees makes humans:

1. Calm down. It didn’t seem this way at first. When us amateurs where putting on our protective suits for the first time there was definitely some nerves. But we had been told about the importance of keeping calm and relaxed while inspecting hives and so we tried out best. Interestingly, in informal conversations many of the beekeepers also talked about how they looked forward to doing their inspections because of how calm the whole process made them feel. So while we did have examples of humans trying to control their own moods, there was also a more relational understanding where the activity of the bees also encouraged particular responses in the humans 2. Become more attentive to whole ecosystems. One beekeeper discussed the way that since they had started, they noticed they were much more aware of the wider environment, including what trees and plants were being grown, whether they were flowering early or late, and cycles in the weather. Another also mentioned how important it is to be aware of the yearly rhythms of potential predators. So forging connections with bees seemed to have a knock on effect of building connections with a much wider variety of living creatures and plants. 3. Develop multiplying practices. One of the first comments at our workshop was the saying that if you put 10 bee-keepers in a room you’ll get 15 different ways of doing things. I thought it was really interesting that bees, which are often used as symbols of regimented order, actually inspire a proliferation of practices and knowledges in the humans that keep them. 4. More intelligent. In a Victorian-era book about encouraging bee-keeping amongst the poor, the author claimed that even while bee-keeping might not always be a success it should be encouraged because it makes people more intelligent. 5. Continuous learners. Paternalism aside, there were many comments about the way the practice of bee-keeping meant that you were always learning more and so always needed to be open to the ways that bees don’t fit with strict models. 6. Drink less alcohol Bees don’t like the smell apparently, so bee-keepers need to moderate their intake, particularly the night before they do an inspection. I wondered how this might affect people’s social lives. Would one have to beg off from a night at the pub because the bees needed looking after in the morning? The video from our first workshop from the AHRC funded In Conversation with...: Codesign with more-than-human communities project, which took place on the 12th-13th of April in Milton Keynes. We worked with the Animal-Computer Interaction Lab at the Open University to think through how participatory design methods might be extended to working with non-humans. |

Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed