|

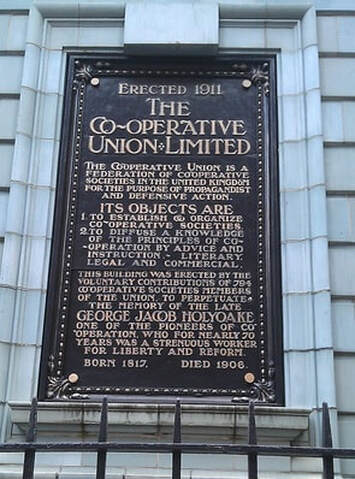

Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy? The Sustaining Time project is funded under the AHRC's Care for the Future theme. In keeping with its aim of 'thinking forward through the past', one strand of our project will scope out the potential of archive resources to provide material for understanding how alternative economic models might challenge dominant approaches to time. The team will be visiting four archives over the course of the project. This post by Alex Buchanan is the first in a series that looks at how we've approached the task of finding time in the archives.  Our first archive visit was to the National Co-operative Archive. This was a great place to start our research, in part because of the way the archivists have helped to make their resources accessible. As I'll explain in this post, the level of detail used in the archive descriptions enabled us easily to identify items which might be of interest and to order them from storage before we arrived. This won't be the case at other archives we visit, so I'm going to use this post to explore how archivists' work can support research, whilst recognizing that such efforts aren't always possible. Since the nature of our research is so specific, i.e. finding out how those experimenting with economic systems might be thinking about time, we will have to put in some additional effort to understanding both the domain and the archives we use in order to get the most out of these resources. There are 6 ways of searching the Co-op archive online, including an image search, which we did not use. In line with most users' preferences, the default option is a simple free text search. We used this to identify the majority of the items we used, by using keywords including: time, hour/s, work, working, clock/s, future, nature, change, evolution, progress, history, environment, flood/s, earthquake/s, disaster/s. However, as our list of search terms suggests, the disadvantage of this method is that even changing the word from singular to plural brings a different list of results, because the search engine simply looks for exact matches anywhere in a description. This creates a number of problems when trying to research time in the archives. A good example was our search for 'clocks'. Anyone looking for clocks may also be interested in watches, but because the word has another, more common meaning this can confuse the results. In our case, all the item descriptions that included the word 'watch' were for images involving onlookers. This means that it is possible that the Co-op archives include information about pocket and wrist watches (these were often retirement gifts for long serving employees in many businesses, for example), but unless the archivist has included the word in the item description it will not be accessible via a keyword search. One of the ways archivists try to deal with this and other problems associated with keyword searching is to 'index' archives - that is to say, to associate the description with a number of 'authority terms' which the cataloguer decides have particular relevance for the unit being described. At the Co-op archive there are indexes for names (of people and organizations), subjects and places. Authority terms are created as a separate exercise and can involve considerable research, to ensure that, for example (and, not, as far as I am aware, featuring in the Co-op Archive), Robert Smith, equestrian, son of Harvey Smith, is not confused with Robert Smith, musician, lead singer in The Cure. When used consistently, indexes can often be the most efficient and effective means of searching - but they are labour intensive to create. Of the three types of index, subject indexes are perhaps the most problematic for archives. From the point of view of an archivist, archives are not in the first instance information resources because - unlike books - this is not the purpose for which most records were created. Most records are created as evidence - to provide a persistent representation of a time-delimited event. Minutes from meetings provide a good example of this. As the influential archival writer Sir Hilary Jenkinson (1882-1961) declared, they 'were not drawn up in the interest of, or for the information, of posterity'. The American archival theorist T.R. Schellenberg modified this perspective, by suggesting that archives have two sets of values: primary values for their creators and secondary values for other users, which come into play in particular when records, created for current purposes, cross the 'archival threshold' and then may be used by a wide variety of users for a wide variety of purposes. Archivists want to open the records in their custody to the widest variety of users and uses. Subject indexing is intended to assist with this but archivists cannot predict all the possible topics future researchers may want to investigate. Trying to represent the subject matter of a document from the perspective of its creator/s follows archival theory's traditional emphasis on provenance (discussed further below) and thus appears theoretically straightforward, although it inevitably involves difficult decisions in practice, as anyone who has ever tried to describe a photograph without knowing what the photographer was trying to capture will recognize. Extending this indexing to include possible research topics is fraught with difficulties and is thus rarely attempted: a more common approach is the 'Subject Guide', whereby an archivist gathers together potential resources for a researcher interested in a particular subject area. However, when embarking on this research, we were aware that the elusive nature of time and temporal awareness was one of the difficulties we would have to overcome (which will be explored in our 'Methods Festival' in June) - there are no useful archive guides on temporal research to assist us. Archivists' descriptions try to represent the context of creation of the records - this is what is known as 'provenance'. Whilst archives can be used to support an almost infinite variety of research topics, which will inevitably change over time, it is generally accepted that our understanding of the people and processes that created the records in the first place are likely to remain relatively constant and that this knowledge is vital for interpreting the records' historical meaning. This means that archivists try to maintain the original order of the records, and list them according to their creators. Thus at the Co-operative Archive, all the records of the Crumpsall Biscuit Works are described as a single group. They are, of course, not all the records created - the vast majority have not survived, but enough remained for us to get a sense of the importance the Co-op movement accorded both to worker welfare and to production efficiency in this model factory. In an archive where descriptions are less full than at the Co-op, the only way we may be able to identify records relevant to our research will be by identifying the types of organizations and the historical circumstances which might produce records of potential interest. Again, by starting with an archive with a very detailed catalogue, we have started to build up a picture of what sorts of series of records are likely to be of particular significance to our research. In a later post, I'll explore how 'Time' is represented in other forms of resource discovery, such as library catalogues. Alex Buchanan Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy? Written by Alex Buchanan (University of Liverpool)  mystuart (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) mystuart (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) In our previous post, we described some of the changes in the baking industry following the deregulation of bread prices in the UK in 1815. In this post we wanted to outline some of the temporal dimensions specific to baking that have been revealed in our preliminary research: Night-working. Long hours worked at night were the main factor that set baking apart from other crafts. Night working was promoted both by the consumer (wanting to purchase fresh bread before work in the morning) and the supplier (the journeyman working on commission, who needed to buy the amount of flour agreed with the miller or corn factor). The introduction of the free market encouraged longer hours and during the nineteenth century, bakers might have only 4-5 hours sleep each day. Yeast - bread-making was a lengthy process, needing to take into account the cycles of rising and kneading. Until the production of dried yeast, it needed to be nurtured as a living product, in the forms of barm or ferment - which remains true of traditional sourdough bread. In 1859 the aerated bread process, which needed no yeast, was patented by Dr John Daulish, founder of The Aerated Bread Company. This reduced the length of time taken in breadmaking from around 10 hours per loaf to around 2 - but the high costs of the machinery limited its take-up. Perishability - this limited bread production to the locality and required consumers to make regular purchases. In a fascinating article on the Halifax (Canada) baking and confectionary industry, we found a quotation from an 1868 petition by the Journeyman Bakers' Friendly Society "To the Master Bakers of Halifax", which puts the workers' hours of labour into a social and moral context designed to resonate with public opinion on respectability. In a moral and intellectual point of view it is nearly as bad, as we have no time for recreation, no moral improvement; no time to spend in the social or family circle. We have no time for the public meeting, lecture, concert or religious duty; the Sun shines in vain for us, the trees and plants may grow, and the flowers may bloom, but not for us. To us the delights of the country are a sealed book; to prepare for our early toil we have to go to bed, (those that have one), while the rest of the world is awake, and work while the rest of the world asleep, thus reversing the laws of nature. No wonder that some of us have recourse to stimulants in order to give a spur to our overworked and failing nature, and for the time to bury in oblivion our degraded position.' Modern breadmaking methods have reduced the need for night working, by cooling dough down to low temperatures - its fermentation is then halted until it is warmed up again. Modern methods, including par-baking and the use of steam ovens, have even enabled bread to be transferred directly from freezer to oven. The use of frozen dough has allowed for the introduction of on-site baking and the continuous supply of fresh bread in supermarkets etc. The return to artisan baking, however, means that some of the time conflicts experiences by bakers in the 1800s are being re-visited today. We’ll explore this in our next post.

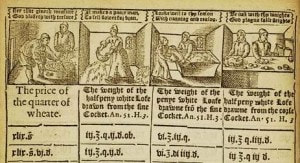

References: Burnett, J., 'The Baking Industry in the Nineteenth Century', Business History, 5/2 (1963), pp.98-108 Collins, E.J.T., 'Food adulteration and food safety in Britain in the 19th and early 20th centuries', Food Policy, 18/2 (1993), pp.95-109 Decock, P. and S. Cappelle, 'Bread technology and sourdough technology', Trends in Food Science & Technology, 16/1-3 (2005), pp.113-20 Gourvish, T.R., 'A Note on Bread Prices in London and Glasgow, 1788-1815', The Journal of Economic History, 30/4 (1970), pp.854-60 McKay, I., 'Capital and Labour in the Halifax Baking and Confectionary Industry during the last half of the Nineteenth Century', Labour/Le Travail, 3 (1978), pp.63-108 Ross, A.S.C., 'The Assize of Bread', The Economic History Review, 9/2 (1956), pp.332-42 Stern, W.M., 'The Bread Crisis in Britain, 1795-6', Economica, n.s. 31/122 (1964), pp.168-87 University of Durham, Special Collections and Archives, 'Bread through the Ages', available at http://www.dur.ac.uk/~dul0www3/asc/bread/control1.htm Webb, S. and B., 'The Assize of Bread', The Economic Journal, 14 (1904), pp.196-218 Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy? This post was written by Alex Buchanan (University of Liverpool) For many people the new economics is synonymous with the rise of the artisan economy. One of the flagships for this movement is the revival of artisan bread, which includes the rise of community bakeries, such as Homebaked Anfield and the campaign for Real Bread. In order to start to tease out the relationships between time and alternative economies we’ll be including case studies of a variety of new artisan businesses. However, we’ve also been really interested in the way many approaches to the new economics explicitly draw on the past for inspiration. So we will also be exploring how archive research might shed light on contemporary questions about economics and time. We’ve been doing some preliminary research into what kinds of records might give insights into baking methods and cultures. Part of this involved finding out more about the history of the baking industry, to identify what records might have been created. This research has already thrown up some interesting findings which relate to the time-dimension and economics of baking.  Woodcut showing the making of bread in bakeries, from The Assize of Bread 1608 Woodcut showing the making of bread in bakeries, from The Assize of Bread 1608 Until 1815, bread-making was controlled by medieval legislation: the 'Assize of Bread' of 1266. This stipulated the size, weight and price of loaves according to the price of wheat and included other regulations for bread production. A number of books listing sizes and prices of loaves survive: we looked at one in the Liverpool University Special Collections as part of the 'Memories of Mr Seel's Garden' project; there's another one online here. The Assize did not prevent price fluctuation, but linked it to the grain market. Rather than competing against price as we do now, under this system, competition between bakers was based on bread quality, as it was illegal to produce cheaper loaves. This ideally led to better tasting bread, rather than simply cheaper bread. Although in times when flour was expensive, adulteration was common. During the eighteenth century, however, the monopoly of the craft guilds was breaking down and increasing numbers of bakers (often not master bakers, but journeymen acting as agents for millers and flour merchants) began to undercut the fixed price - and were hailed as the champions of liberty against the bastions of ancient privilege. After the end of the bread crisis and famine years of the late 1790s, many towns abandoned the Assize and a Parliamentary Committee appointed to enquiry into the matter in 1815 recommended that more benefits were likely to be incurred from free competition.

The actual results of deregulation, however, were revealed by H.S. Tremenheere's 1862 Report Addressed to Her Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for the Home Department, relative to the Grievances complained of by Journeymen Bakers, with Appendix of Evidence, 3027, H.C. (1862). This documented an industry still dominated by artisan methods but in appalling conditions and for low financial reward, with prices kept down by low wages and adulteration. In particular, alum was added to flour to meet public demand for 'white' bread - perceived as being purer and therefore of higher quality. Under these circumstances, author John Burnett, writing in 1963, viewed the introduction of technology and changes brought by improved scientific understanding of the baking process, as well as the importation of grain from further afield, as advances which 'rescued the journeymen from the miseries of 1862'. We’ve found a number of interesting transformations in senses of time occurring during the process of deregulation, which we will outline in our next post. Alex Buchanan |

Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed