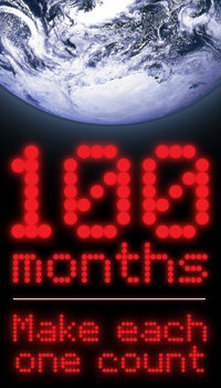

Originally published on the Time of Encounter Blog, part of an AHRC funded project that looked at time in social life I was at the World Open Space on Open Space event in London this weekend. For those of you who don’t know, Open Space Technology is a technique developed by Harrison Owen that allows groups to self-organise conferences. Rather than setting out a schedule in advance, participants create the schedule in the first session of the day. I’ve been interested in how this technique might offer one way of experiencing time differently from more normal conferences which often feel rushed and cut off by clock time. So at the WOSonOS meeting yesterday I proposed a session on OS and time and ended up having a really great wide-ranging conversation. I’m hoping to write up my thoughts on this in more detail, but in the mean time you can read a report on our discussions here.  Originally posted on the Time of Encounter Blog, part of an AHRC-funded project looking at time in social life. This month the New Economics Foundation’s One Hundred Months Clock hit its halfway point. Developed by Andrew Simms and Peter Meyers, it is a new kind of clock for our time of climate change. Like the Doomsday Clock, the One Hundred Months clock provides an important contrast to the way the regular clock projects an empty or open future. Instead of a time that ticks on the same forever, this clock has a beginning and an end. Started in August 2008, it indicates the number of months that NEF suggest are still available for us to take action to avoid runaway climate change. Working on the assumption that we need to avoid raising the Earth’s average surface temperature by more than 2ºC, they argue that if we have not made significant progress within this time period, it will be too late. (See here for the technical report [PDF]). One of my favourite ways of quickly explaining to people why clocks are not objective or neutral is to say that while I can look at the clock and tell if I’m late for work, I can’t look at the clock and tell if I’m too late to respond to climate change. I wonder if Andrew Simms had some of the same thoughts. In the first post on the clock, written for the Guardian, he describes tired office workers anxiously watching their wall clock on that Friday in August, looking forward to going home. For him there seemed to be a disconnect between the vast global changes taking place and the world this kind of clock focuses us on – work, holidays, football transfer schedules. In creating the One Hundred Months Clock he writes that “there is now a different clock to watch than the one on the wall”. Rather than suggesting that every future moment will provide more opportunities to act, this new clock instead “tells us that everything that we do from now matters”. What I really like about this clock then is the way it explicitly challenges the assumption that everyday clocks are all-encompassing. Instead it points out that those clocks we stare at while at work actually hide some of the most important changes that are happening in the world at the moment. Watching the countdown on the website, instead of the one on the wall, perhaps we could begin to coordinate ourselves in different ways around new understandings of what is significant. Visually the clock recalls a bedside alarm clock, with a dash of a countdown-clock-at-a-sports-arena vibe. The red digital display shows the remaining months, days, hours and seconds until the window of opportunity for action closes. Like a traditional clock, and unlike the Doomsday Clock, it is not responsive to any actions we take in the meantime, but keeps ticking on regardless. This experience of time ticking away is reinforced by the tick, tick, tick that you can hear on the website, a ticking that also sounds like a bomb waiting to go off. As if to acknowledge the anxiety the sound can create the website provides a mute button. Interestingly this countdown often gets confused with the kind of time told by the Doomsday clock. That is a lot of people seem to assume that NEF are predicting the actual end of the world (see the comments on this article for example). But it’s not as simple as this. Indeed another intriguing aspect of the clock is that it uses a very linear idea of time to actually tell a story about the non-linearity of climate change. In some of the first e-bulletins sent to those who signed up to the movement, there are a range of videos and links that focus on climate feedback loops and tipping points. Capitalising on new understandings of how climate change works, the clock suggested that these processes are not linear, but instead it harks back to ancient Greek ideas of kairos and chronos, where kairos refers to those specific times when action is possible. Instead of every moment being equal, the clock tells us that these hundred months are unlike any other. As one of narrators says in one of the video links: “those who came before us didn’t know anything about this problem, and those who come after will be powerless to do anything about it, but for us there’s still time, we better get a move on though” (from Leo Murray). The clock is not counting down to Doomsday then, but rather to the end of the window opportunity, the end of the kairotic moment. One of the things I’m wondering about, though, is how the One Hundred Months Clock might change the way we understand our relatedness, with each other and with the world. Fundamentally, as I’ve argued previously, clocks are devices for coordinating ourselves with what is significant to us, and this new clock does offer a different take on what is significant from our usual clocks. But I’m not sure whether it yet provides the kinds of mechanisms of re-coordination that are also needed. The monthly e-bulletins, for example, offer suggestions for actions to take each month, asking readers to ‘let’s make this month count’. But I found that a lot of these suggestions are to sign petitions, lobby politicians or attend one-off events. The power to act seems to remain within the realms of trying to convince politicians and large companies to act responsibly. Reading through the actions also felt a little isolating, they were often about things I would do alone. As a result, the One Hundred Months Clock ended up reminding me too much of that bedside alarm clock. The red numerals reminding me of all the times I’ve stared at my alarm, feeling out of synch with everyone else. Either not wanting to get up, or not being able to get to sleep – a kind of limbo where there are either not enough people around to do what you want, or where there are too many expecting you to do too many things you might not want to do. I’d like to venture that for many of us, this is exactly what the ‘time of climate change’ feels like. But if we are to seize the opportunity offered by the next fifty months then this problem of community – of acting with others in ways that feel significant but also achievable – is something that our clocks will also need to tell us about. To do this will require some radical experiments with what a clock is or could be (and I’ll be exploring examples of these in future posts) but, fundamentally, the awareness that, as Simms points out, we do indeed need other ones. ———-- Update: Forgot to say, that I’ve not yet had a chance to read through the suggestions made in the 50 months to save the world feature released yesterday, but I have the feeling that the question of relationality, or community is addressed in a variety of ways in these posts.. Will write something up about it when I can. |

Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed