|

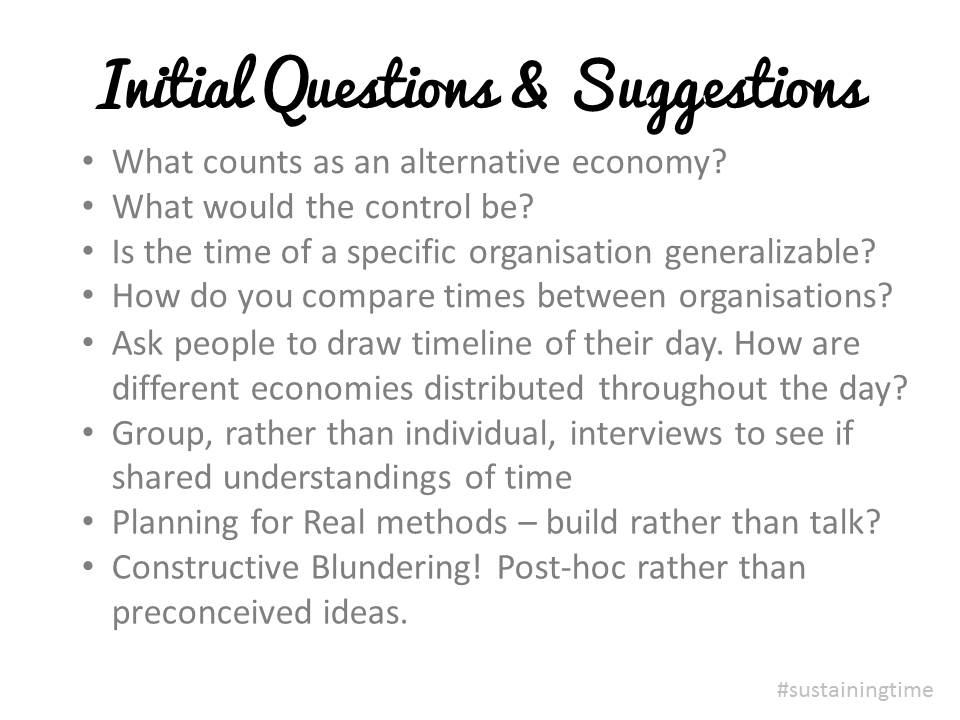

Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy? A key question for us since we first started thinking about this project, was not only what is the time of sustainable economies, but how we might find it. How on earth do you actually go about researching people's perceptions of time? As anthropologist Kevin Birth writes eloquently in his paper Finding Time: Studying the Concepts of Time Used in Daily Life: Cultural conceptions of time do not lie by the side of the road waiting for an ethnographer to wander by and pick them up. Indeed, the idea of the naïve fieldworker walking up to some beleaguered informant and asking, “What are your cultural ideas of time?” is amusing in its absurdity. There is something about time that makes it seem extremely important to understanding how people live, yet it seems an intangible concept. It seemed to us that the project provided a great chance to address a series of interesting methodological questions. Work that has come out of the AHRC Connected Communities theme, for example, has raised a number of questions about the ability of established research methods to do justice to the dynamic nature of communities (see particularly McLeod & Thomson 2009; Law 2004; Abbott 2001). They suggest that need to understand communities as being in time, (or even as producers of time), just as much as the more usual focus on communities and space, territory, locality etc. We were also intrigued by the development of methods for researching experiences of space as changing and dynamic, which have been coming out of the mobilities research paradigm (Buscher, Urry, Witchger 2011). What methods might researchers use to study the way time itself can also be changing and dynamic, rather than simply assuming that time provides a taken-for-granted background to everyday life? Since the remit of this project was, above all, to be exploratory, we created a variety of opportunities for us to reflect on methods as the project progressed. We asked for advice from our Project Partners and Advisers and I've summarised their suggestions in the slide below: In some ways the approaches we have been using are perhaps on the more conservative side, in that we are focusing primarily on archival research, participant observation and open-ended focus group interviews. Even so we've been finding that attempting to use these methods to research the slippery subject of time has ended up working back on the methods themselves. You can read about Alex's experiences in the archives here and here, for example, and we'll be adding further reflections as we go along.

But given that we were also aware that there are a wide variety of other methods that have been developed, we were excited to be able to include a Methods Festival for Studying Perceptions of Time, which took place on the 26th of June 2013. Organised by Jen Southern, this event explored the potential of arts, design and technology practices for researching shifting temporal paradigms, as well as a number of different ways that social science methods have been put to use in studying time. The talks from this event are now online and can be accessed here. References Abbott, A. (2001). Time Matters: On Theory and Method. Chicago, University of Chicago Press. Birth, K. (2004). "Finding Time: Studying the Concepts of Time Used in Daily life." Field Methods 16(1): 70-84. Bryson, V. (2008). "Time-Use Studies: a potentially feminist tool?" International Journal of Feminist Politics 10(2): 135-153. Büscher, M., J. Urry, et al., Eds. (2010). Mobile Methods. Abingdon, Routledge. Law, J. (2009). After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. Abingdon, Routledge. McLeod, J. and R. Thomson (2009). Researching Social Change: Qualitative Approaches. London, SAGE.  The write up from the recent Festival of Methods for Studying Perceptions of Time is now available on-line. Get an overview of what we got up to, listen to the presentations and have a look at the resources created on the day. Organised by Jen Southern as part of the Sustaining Time project. Speakers include: Rachel Thomson (Sussex), Martin Green (Lancaster), Alex Buchanan (Liverpool), Helen Holmes (Sheffield), Jennifer Whillans (Manchester), Eric Laurier (Edinburgh), James Ash (Northumbria), Jen Southern (Lancaster) and Chris Speed (Edinburgh). Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy? Written by Alex Buchanan (University of LIverpool) The Sustaining Time project is funded under the AHRC's Care for the Future theme. In keeping with its aim of 'thinking forward through the past', one strand of our project is scoping out the potential of archive resources to provide material for understanding how alternative economic models might challenge dominant approaches to time. The team will be visiting four archives over the course of the project. This post by Alex Buchanan is the second in a series that looks at how we've approached the task of finding time in the archives.  The Working Class Movement Library by Andrew Nić-Pawełek (CC BY-SA 2.0) The Working Class Movement Library by Andrew Nić-Pawełek (CC BY-SA 2.0) My most recent archive visit was to the truly inspiring Working Class Movement Library (WCML) in Salford. The WCML was established as a labour of love by Eddie and Ruth Frow, lifelong members of the Communist Party, who dedicated their leisure time to collecting books, archives and memorabilia recording over 200 years of working class history. When the collection outgrew the Frows’ own house, it was moved to the present location, a Victorian former nurses’ home in Salford Crescent. It has received a number of grants, notably from the Heritage Lottery Fund, to ensure that the collections are catalogued and accessible – an ongoing task managed by both a professional staff and an enthusiastic team of volunteers, of which Ruth Frow was a member until her death in 2008. The enthusiasm of the Frows – and their supporters – for working-class history is in itself reflective of an attitude to time which demands the memorialisation of historical events – and the people involved, whether or not their names survive – in order that they may inform and inspire those who follow in their footsteps. Marx’s work, deeply informed by his understanding of history, ensured that his followers have been equally keen to trace the seeds of historical change, which might document the potential for revolution. Thus the collection in itself is a document of a particular temporal awareness, which is also obviously present within its contents. A single example will suffice: a booklet printed as part of the celebration of the Dorsetshire Labourers’ Centenary in 1934. This event, staged in collaboration with the Trades Union Congress, commemorated the Tolpuddle Martyrs, the Dorset farmworkers sentenced to transportation to Australia as convicts for joining together as a union in 1834. The centenary involved a number of activities designed to raise awareness of the historical dimensions of trade unionism, including an elaborate series of tableaux telling the story of events in Tolpuddle. In the words of Labour M.P. Arthur Greenword, quoted in an advertisement for the Co-operative Printing Society Ltd (printers of the leaflet): 'What we as workers have lacked, is tradition, and now we are building it.’  Charles Bedaux with filmmakers Charles Bedaux with filmmakers Thanks to the useful catalogue and the knowledgeable guidance of former librarian Alain Kahan (for which I am extremely grateful), I identified a number of other useful resources which will repay further study and a number of record types and historical episodes which we can try to explore in the collections of other repositories. In scoping the ‘Sustaining Time’ project, we identified that useful archive material was likely to be generated as a result of industrial disputes – and this proved very much the case at the WCML. Two particular themes emerged: industrial workers’ concerns about new ‘scientific’ management techniques which involved time and motion studies, and ‘white collar’ unions’ concerns about ‘flexi-time’, that is to say working practices involving changes to working hours. In terms of management, business historians have already identified that in the UK, neither the so-called scientific techniques of the famous Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915), nor the production-line management of his fellow American, Henry Ford (1863-1947), were as directly influential as the approach of Charles Bedaux (1886-1944), whose management consultancy business had a branch in London. Much research has been devoted to charting the spread of modern management in the UK and numerous firms, including Vickers Instruments, Rover cars and ICI have been shown to have adopted Bedaux methods. Other firms are known to have overhauled their processes without employing efficiency engineers – the new approach soon became an essential tool of modern management. What is particularly fascinating about the WCML’s collections is that they provide a glimpse into the other side of the picture – the reaction of the workers to these new methods of control, which extended to the imposition of particular bodily actions in order to increase efficiency (and reduce fatigue). In the archive is a file of legal papers drawn up as part of a dispute between members of the Wiredrawers’ Union and Richard Johnson and Nephew, of Bradford, Manchester in the 1930s. These provide an insight into the workers’ objections, which focused in particular on their unease at the use of stopwatches to time workers’ actions. This was felt to be an attack on the industrial expertise and autonomy of the employees, who valued their identity as highly skilled craftsmen. Sadly for them, their long strike did not achieve its aims of rejecting Bedaux, nor were the strikers eventually reinstated – however they received much local and national support and much publicity for their cause. My next archival trip will be to the Modern Records Centre at Warwick University, where I expect to find more information about opposition to the Bedaux system and other worker campaigns over attempts to control their temporal autonomy. Earlier this year I was lucky enough to be invited to attend the 2013 IASH Winter School on Timing TransFormations as a post-doctoral participant. The team have added videos of some of the attendees talking about their work. See Rosi Braidotti, Antje Fluechter, Elaine Gan and others on the importance of time in their work. I spoke a little about why I think philosophy should pay more attention to the subtleties of clock time in social life. |

Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed