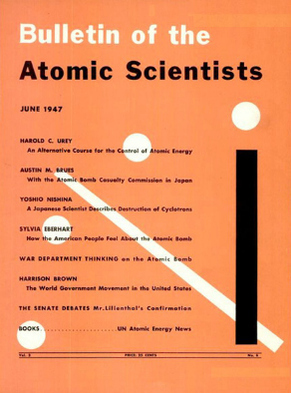

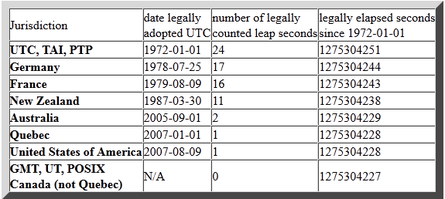

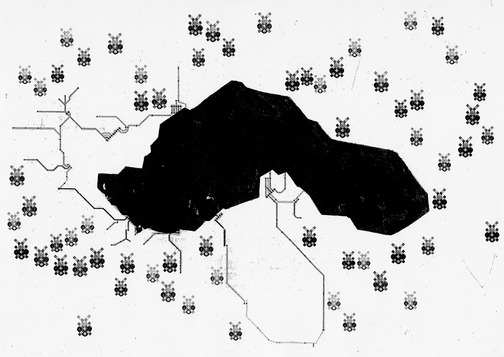

Clock of the Long Now prototype (CC piglicker) Clock of the Long Now prototype (CC piglicker) Originally published on the Time of Encounter blog, part of an AHRC funded project exploring social aspects of time. Fittingly, on the first day of the 14th Baktun, I want to continue with my focus on the Clock of the Long Now and the question of its ability to support a wider appreciation of deep time. For Brand, the “ambition and folly of the Clock..is to reframe human endeavour, and to do so not with a thesis but with a thing” (1999, 48). And so in this post, I want to focus, not so much on the theory of the clock, but more on the practicalities involved in actually building it, and particularly financing such a large and complex project. While the plan is to build multiple clocks around the world, the construction of the first clock is currently underway in West Texas on the property of Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos after he agreed to back the project to the tune of approximately $42 million. (You can find a great overview of the process from Dylan Tweney here). The site the Long Now Foundation had originally bought in Nevada is now being held in reserve for a second clock. Asked how he justifies spending such a large amount of money on a seemingly impractical project, Bezos told Wired’s Tweney that long-term thinking is just simply worth it, but also that ‘no other billionaire is building a clock like this, for the sole purpose of changing humanity’s relationship to time’. In much of the commentary on Bezos and the Clock of the Long Now there seems to be agreement that this is almost a match made in heaven. Bezos is well-known throughout the tech industry for being a long-term thinker. As he notes himself in an article for IEEE Spectrum his first letter [PDF] to Amazon.com shareholders in 1997 set out his interest in pursuing “long-term market leadership considerations rather than short-term profitability considerations”. His early investment in ebook readers is often cited as clear example of this priority of the long-term over the short. While the development of Amazon Web Services, and in particular the long-term online storage facility Glacier, could actually be seen to address some of the issues around short-term thinking in the tech world that Danny Hillis initially sought to respond to with his clock project (see my previous post). As Bezos has said in a number of contexts, one of the three basic rules of Amazon is “patience. We are looking at the long term. We know how to wait for results.” But what if we take a wider-view of clocks and the time of Amazon? In my first post, I suggested that understanding the role of time in social life would be helped by using a broader definition of the clock. Where a clock, is not an objective tool for measuring a single smooth flow of perpetual change, but as a device for social coordination, which was encoded with social values and produced through social decisions about what is important and what is not, what we need to be synchronised with and what we can ignore. What I want to suggest is that when we look at time in this way, the relationship between the Clock of the Long Now and Amazon doesn’t appear quite so felicitous. Fundamentally, while the Clock of the Long Now is trying to make long-term thinking automatic for those who experience it, the aim of Amazon is arguably to provide an experience of speed and immediacy. Each new innovation, from One-Click Ordering, Amazon Prime, the Kindle and even the long-term storage service provided by Glacier is guided by the desire to decrease the amount of patience asked of those who use its services. In conjunction with this we must also consider the high-pressure experiences of those working for the company itself and particularly the workers at the company’s fulfilment centres who must work at an extremely fast pace on short-term flexible contracts. If Bezos is serious about ‘changing humanity’s relationship to time’ shouldn’t he pay attention to the much wider changes his company is already facilitating? Can the Clock of the Long Now really compete with the Clock of Amazon?  Used under CC license Scottish Goverment Used under CC license Scottish Goverment How, for example, can its fulfilment centre workers think about the long-term when they have no security of contract? How can companies think about the long term, when Amazon claims that is Glacier service means that “customers no longer need to worry about how to plan and manage their archiving infrastructure”. While letting Amazon worry about the long term may sound attractive, as Brand and Hillis have claimed, many of their most interesting innovations have been produced through grappling with the concrete task of building the Clock. What Glacier does is allow the customer to lose the opportunity to learn more about the process of long-term thinking, as this can be outsourced to Amazon. More generally, Bezos’ focus on the customer’s experience centres on meeting the desire for a wide range of goods delivered fast at the cheapest price. But as Pheobe Sengers has suggested in her fascinating piece on time, technology and the pace of life, it is actually when you don’t have a great deal of choice, and can’t get things quickly that you start experiencing time in a more sustainable and relaxed way. What the Clock of Amazon allows is actually the ability to ignore the long term, to value immediacy and to act on fleeting impulses rather than make well thought out decisions. In Amazon’s defence, Brand writes in his book on the Clock of the Long Now that the project is not interested in slowing everything down. Instead he argues that it is actually the “combination of fast and slow components [that] makes the system resilient, along with the way the differently paced parts affect each other. Fast learns, slow remembers. Fast proposes, slow disposes. Fast is discontinuous, slow is continuous…Fast gets all our attention, slow has all the power. All durable dynamic systems have this sort of structure; it is what makes them adaptable and robust” (34). He suggests that commerce is one of the ‘fast’ systems of a culture, while other areas such as infrastructure and governance are slower and help moderate its excesses. From this point of view, perhaps the Clock of Amazon might not so problematic. Crucially, however, this rests on the assumption that governance structures are strong enough to shape businesses in particular ways and according to longer-term priorities. The reality seems to be further and further from the case. The consequences of paying poverty wages, of increasing inequalities between the poor and the rich and the repercussions of Amazon’s failure to contribute to broader social structures through its widespread tax avoidance are all long-term issues that Amazon is very clearly not being required to address. The idea of the Long Now came from Brian Eno, who after climbing over homeless people on a building’s steps in order to visit a glamorous loft owned by a celebrity, realised that for her ‘here’ stopped at her front door and ‘now’ meant this week (Brand 1999, 28). Shocked by the contrast between the poor and the rich he wrote that he wanted to be living in a ‘Big Here and a Long Now’. This is one of the fundamental ideas the Clock is based on. The risk in allying this understanding of the long-term with Bezos’ is that much of its radical nature could be lost, and the Clock of the Long Now could have very little chance of competing with the other ‘clock’ Bezos is also building. Reference Brand, Stewart. 1999. The Clock Of The Long Now: Time and Responsibility. New York: Basic Books Sounding Drawing is one of the three projects that make up the Time of the Clock, Time of Encounter project and was led by Anne Douglas, Kathleen Coessens, Mark Hope and Chris Freemantle (On the Edge (OTE) Research, Woodend Barn Arts Centre, Orpheus Research Centre in Music (ORCiM), Champ’D’Action, and Ecoarts Scotland). It involved a practice-led experimentation in and improvisation around linking sound and image. In the second workshop participants were asked to create a 'score' for a drawing. The groups came together almost by chance or instinct and I found myself in a group with Fiona Hope and Isaac Barnes where we collaborated on 'sounding' Ann Eysermans P6. You can hear the results just below.  Originally published on the Time of Encounter Blog, part of an AHRC funded project that looked at time in social life I was at the World Open Space on Open Space event in London this weekend. For those of you who don’t know, Open Space Technology is a technique developed by Harrison Owen that allows groups to self-organise conferences. Rather than setting out a schedule in advance, participants create the schedule in the first session of the day. I’ve been interested in how this technique might offer one way of experiencing time differently from more normal conferences which often feel rushed and cut off by clock time. So at the WOSonOS meeting yesterday I proposed a session on OS and time and ended up having a really great wide-ranging conversation. I’m hoping to write up my thoughts on this in more detail, but in the mean time you can read a report on our discussions here.  Originally posted on the Time of Encounter Blog, part of an AHRC-funded project looking at time in social life. This month the New Economics Foundation’s One Hundred Months Clock hit its halfway point. Developed by Andrew Simms and Peter Meyers, it is a new kind of clock for our time of climate change. Like the Doomsday Clock, the One Hundred Months clock provides an important contrast to the way the regular clock projects an empty or open future. Instead of a time that ticks on the same forever, this clock has a beginning and an end. Started in August 2008, it indicates the number of months that NEF suggest are still available for us to take action to avoid runaway climate change. Working on the assumption that we need to avoid raising the Earth’s average surface temperature by more than 2ºC, they argue that if we have not made significant progress within this time period, it will be too late. (See here for the technical report [PDF]). One of my favourite ways of quickly explaining to people why clocks are not objective or neutral is to say that while I can look at the clock and tell if I’m late for work, I can’t look at the clock and tell if I’m too late to respond to climate change. I wonder if Andrew Simms had some of the same thoughts. In the first post on the clock, written for the Guardian, he describes tired office workers anxiously watching their wall clock on that Friday in August, looking forward to going home. For him there seemed to be a disconnect between the vast global changes taking place and the world this kind of clock focuses us on – work, holidays, football transfer schedules. In creating the One Hundred Months Clock he writes that “there is now a different clock to watch than the one on the wall”. Rather than suggesting that every future moment will provide more opportunities to act, this new clock instead “tells us that everything that we do from now matters”. What I really like about this clock then is the way it explicitly challenges the assumption that everyday clocks are all-encompassing. Instead it points out that those clocks we stare at while at work actually hide some of the most important changes that are happening in the world at the moment. Watching the countdown on the website, instead of the one on the wall, perhaps we could begin to coordinate ourselves in different ways around new understandings of what is significant. Visually the clock recalls a bedside alarm clock, with a dash of a countdown-clock-at-a-sports-arena vibe. The red digital display shows the remaining months, days, hours and seconds until the window of opportunity for action closes. Like a traditional clock, and unlike the Doomsday Clock, it is not responsive to any actions we take in the meantime, but keeps ticking on regardless. This experience of time ticking away is reinforced by the tick, tick, tick that you can hear on the website, a ticking that also sounds like a bomb waiting to go off. As if to acknowledge the anxiety the sound can create the website provides a mute button. Interestingly this countdown often gets confused with the kind of time told by the Doomsday clock. That is a lot of people seem to assume that NEF are predicting the actual end of the world (see the comments on this article for example). But it’s not as simple as this. Indeed another intriguing aspect of the clock is that it uses a very linear idea of time to actually tell a story about the non-linearity of climate change. In some of the first e-bulletins sent to those who signed up to the movement, there are a range of videos and links that focus on climate feedback loops and tipping points. Capitalising on new understandings of how climate change works, the clock suggested that these processes are not linear, but instead it harks back to ancient Greek ideas of kairos and chronos, where kairos refers to those specific times when action is possible. Instead of every moment being equal, the clock tells us that these hundred months are unlike any other. As one of narrators says in one of the video links: “those who came before us didn’t know anything about this problem, and those who come after will be powerless to do anything about it, but for us there’s still time, we better get a move on though” (from Leo Murray). The clock is not counting down to Doomsday then, but rather to the end of the window opportunity, the end of the kairotic moment. One of the things I’m wondering about, though, is how the One Hundred Months Clock might change the way we understand our relatedness, with each other and with the world. Fundamentally, as I’ve argued previously, clocks are devices for coordinating ourselves with what is significant to us, and this new clock does offer a different take on what is significant from our usual clocks. But I’m not sure whether it yet provides the kinds of mechanisms of re-coordination that are also needed. The monthly e-bulletins, for example, offer suggestions for actions to take each month, asking readers to ‘let’s make this month count’. But I found that a lot of these suggestions are to sign petitions, lobby politicians or attend one-off events. The power to act seems to remain within the realms of trying to convince politicians and large companies to act responsibly. Reading through the actions also felt a little isolating, they were often about things I would do alone. As a result, the One Hundred Months Clock ended up reminding me too much of that bedside alarm clock. The red numerals reminding me of all the times I’ve stared at my alarm, feeling out of synch with everyone else. Either not wanting to get up, or not being able to get to sleep – a kind of limbo where there are either not enough people around to do what you want, or where there are too many expecting you to do too many things you might not want to do. I’d like to venture that for many of us, this is exactly what the ‘time of climate change’ feels like. But if we are to seize the opportunity offered by the next fifty months then this problem of community – of acting with others in ways that feel significant but also achievable – is something that our clocks will also need to tell us about. To do this will require some radical experiments with what a clock is or could be (and I’ll be exploring examples of these in future posts) but, fundamentally, the awareness that, as Simms points out, we do indeed need other ones. ———-- Update: Forgot to say, that I’ve not yet had a chance to read through the suggestions made in the 50 months to save the world feature released yesterday, but I have the feeling that the question of relationality, or community is addressed in a variety of ways in these posts.. Will write something up about it when I can.  Originally posted on the Time of Encounter Blog, part of an AHRC-funded project looking at time in social life. If, as I suggested in my previous post, our everyday clocks obscure the politics involved in their production, there are also a wide variety of clocks that have been explicitly developed to intervene into the political. These clocks do not tell the story of a homogeneous, unending and all-encompassing time, but instead provoke us to re-examine our assumptions about time itself. The first couple of examples I want to focus on in this series intervene into the notion of an undifferentiated future and instead suggest that the end of time might actually be very close to the present. Arguably of the most prominent example of this type of clock is the Doomsday Clock. Created in 1947 by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, it tracks the likelihood of nuclear war. Using a traditional clock-face, the clock re-purposes the minute hand so that it no longer indicates the accumulated changes in the ceasium atom (which is the basis of atomic time) but instead indicates changes in the prevalence of atomic bombs and their likelihood of use. Giving new meaning to the concept of ‘atomic time’, the clock was developed in the early stages of the cold war in order to “frighten men [sic] into rationality” according to Eugene Rabinowitch, one of the co-founders of the Bulletin. Thus while still using the design of the standard clock, this version undoes UTC’s soothing projection of a future without end through a refocusing on the very real possibility of armageddon. In one of the few academic articles about the clock, Juha Vuori suggests that the continued use of the standard design was crucial to lending believability to clock that was more prophetic that precise. He argues that “through the symbol of the Doomsday Clock, the Scientists have been able to combine their social capital as voices of reason and objectivity with that of the soothsayer to influence society and behaviour” (Vuori, 2010 264) Going back to the redefinition of the clock that I proposed in my first post, the Doomsday clock illustrates really nicely the notion that clocks should not be understood simply as devices for telling the time, but as devices for coordinating with what is significant. It initially sought to focus attention on the specific context in 1947. But, although originally designed to be simply a static image, in 1949 the Doomsday Clock was moved forward from seven minutes to midnight to just three minutes in response to the first Soviet tests of the atomic bomb. Later the changing political context led to the clock being moved back back to seven minutes to midnight in 1960. This adds an extra dimension to its disruption of clock time, providing the possibility of time to move forward or backward depending on the political context and human action or inaction. But further it shows the importance of continuing to track significant change when attempting to tell the time. As part of this, later changes to the clock included incorporating an analysis of the threats of climate change and biological weapons. Indeed, the clock was moved forward one minute to midnight in January 2012 in part due to inaction over climate change. (See here for an outline of the changing times of the clock). One thing that the Doomsday Clock suggests, then, is that if you want your clock to remain significant it has to keep with the times. However, what can also be learnt is the difficulty of doing so. A common criticism has been that the clock did not move at all during the Cuban missile crisis, but stayed at seven minutes to midnight throughout. The attempt to make the clock more relevant by considering a variety of global threats could also strain the reach of its symbolism. Further, inspired by the Doomsday Clock the Atlantic decided to develop an Iran War Clock, only to remove all mention of it from its website soon after with no initial explanation. (Although this is now available). Even so, as one online commentator suggests: “whenever you’re curious how near humanity is to destroying itself, you can check the status on the Doomsday Clock homepage. It’s good to stay abreast of this sort of thing so you can plan your schedule around it.”  Testing an atomic clock (Jessamyn (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) Testing an atomic clock (Jessamyn (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) Originally published on the Time of Encounter blog, part of an AHRC funded project exploring social aspects of time. So in my last post I suggested that clocks are not devices for measuring the time, but are instead tools for coordinating ourselves with what is significant to us. This kind of claim chimes strangely with our usual understanding of the clock. Within philosophy and social theory, for example, ‘clock-time’ is the antithesis of lived, subjective ‘temporality’. Far from being about significance, value and choice, clock-time is regularly understood as an objective, quantitative measure of the flow of an all-encompassing time. This division between objective time and a human or lived ‘temporality’, is neatly described by David Couzens Hoy who suggests that while time “can be used to refer to universal time, clock time, or objective time”, temporality “is time insofar as it manifests itself in human existence” (xiii). For philosophy then, clock-time is not about the human, not about death, politics, duration, seasons, cycles or the backwards-forwards movements of memory and hope. Within social theory too clock time is often understood as being divorced from the time of social life. Instead clock-time is that which separates us from the variable rhythms of our lives and supports our insertion into an unrelenting globalised capitalism. As Barbara Adam puts it: Clock-time, which was developed in Europe during the 14th century, no longer tracks and synthesizes time of the natural and social environment but produces instead a time that is independent from those processes: clock-time is applicable anywhere, any time. Context no longer plays a role (123) But is this really the case? Is clock-time really context free? What I want to suggest is that if you look a little more closely at the clock and how it works, a vertiable cavern opens up below you and instead of a linear, dependable, unending time, you actually find that at the heart of quantitative time itself there are multiple political battles about context, significance and value taking place. I’ll give just a few examples here and will be discussing more in later posts. To begin with, there is no such thing as clock-time in the singular. Instead what we normally call clock-time is in fact the product of the negotiation between two different times, International Atomic Time (TAI) and Universal Time (UT1). Atomic time is told in reference to the ceasium atom. Universal Time, on the other hand, is told in reference to the rotation of the Earth. Importantly, these two times do not synchronise with each other, since the Earth’s rotation is variable. It slows down and speeds up, and so in order to remain synchronised with cycles of night and day Universal Time often needs to be adjusted. So while atomic time would seem to provide the precise, regulated time philosophers and social theorists often refer to when they mention clocktime, we do not actually use TAI itself to tell the time. If we did we would become desynchronised with the rotation of the Earth. Instead our clock time (or civil time) is actually a third time known as Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). This time is produced by adding leap seconds to International Atomic Time in order to stay synchronised with Universal Time.  To make it more complicated, different countries adopted UTC at different times and so have legally recognised different numbers of leap seconds. As you can see from the screen shot below, from a website that tracks these differences, in Germany 16 more seconds have legally elapsed than in the U.S. And one province in Canada, Quebec, is one legal second ahead of all the other provinces in the same country. The complicated and contradictory world of time keeping is even further illustrated in this fascinating look at the social and political character of time zones from the BBC. What this all means is that our clocks are not universal and neither are they context-free. Instead they are regularly adjusted in recognition that our desire for objective precision must nonetheless be tempered by the fact that our lives are spent on an unsteadily spinning globe. Interestingly, there are currently debates raging over whether to do away with leap seconds altogether. This is because their unpredictability (they are added irregularly, with six months notice) makes them problematic for systems that use precise time-keeping such as navigational systems, financial systems and the internet. Even still, this debate is not one over how to make the clock free of context, but needs to be read as a process of making choices about what is more important for us to stay coordinated with. We may well end up deciding that staying coordinated with the systems that support our current economic, transportation and communications infrastructures is more significant to us than staying coordinated with the Earth itself. But this is still a choice over what sets of relations and what kinds of communities we value, a choice over which temporal rhythms we think it necessary to stay in touch with, and which we think we can afford to ignore. Michelle Bastian References: Adam, Barbara (2006). “Time.” Theory, Culture and Society 23(2): 119-126. Hoy, David Couzens (2009). The Time of Our Lives: A Critical History of Temporality. Cambridge, Massachusetts, MIT Press.  Corpus Clock at 6:48am Corpus Clock at 6:48am Originally published on the Time of Encounter blog, part of an AHRC funded project exploring social aspects of time. The Time of the Clock and the Time of Encounter is a project that seeks to explore the role of time in the formation and continued production of ‘community’. The project has a number of different strands led by the different project participants. In this post I want to introduce you to the strand I’ll be working on – “Redefining the Clock”. A lot of philosophical work on time assumes that there are two key aspects of time – an objective time, epitomised by the clock, and a subjective experiential time or non-linear temporality. I have always found this to be extremely problematic because it fails to respond to the large amount of work in anthropology and sociology that argues for the need to understand much of what we call ‘time’ as a social phenomenon. Failing to see the conceptualisation and production of time as a social process means that the role of time in social inclusion and exclusion, in the production of power and legitimacy, in the shaping of understandings of agency, change and success is often not even acknowledged and is currently not adequately explored. What I want to suggest then, is that we need a more adequate philosophical engagement with the clock if we are to understand what we really mean by time in social life. Part of this will involve redefining what we mean by clock. The OED suggests that a clock is “an instrument for the measurement of time; properly, one in which the hours, and sometimes lesser divisions, are sounded by strokes of a hammer on a bell or similar resonant body”. For me this includes too many assumptions, including of course an assumption about the nature of time, but also is too shallow an understanding of the clock to really capture the work it does within social life. In a forthcoming article with the Journal of Environmental Philosophy, Fatally Confused: Telling the Time in the Midst of Ecological Crises, I’ve suggested instead that a more adequate definition of the clocks would be something along the lines of “a device that signals change in order for its users to maintain an awareness of, and thus be able to coordinate themselves with, what is significant to them”.* Here I suggest that a clock is not an objective tool for measuring a single smooth flow of perpetual change, instead it is a device of coordination, a device encoded with social values, and produced through social decisions about what is important and what is not, what we need to be synchronised with and what we can afford to ignore. I’m going to unpack this approach in a variety of ways in the project and will be blogging about it along the way. In my next post I’m going to talk about what might be thought of as standard clock time and show some of the contingent collective decisions that go into its construction. But I’m also going to look more widely at artistic and and scientific interventions that have attempted to shift shared experiences of time through the development of new ‘clocks’. This is partly in order to articulate the historical and comparative context within which The Time of the Clock and the Time of Encounter is situated. But I’m also interested in exploring how an analysis of interventions such as the Doomsday Clock, the Clock of the Long Now and the 100 Months Clock, as well as the Encounters Shop projects by community arts organisation Encounters Arts, might work back on philosophical accounts of time. Stay tuned… * You can now access this article here |

Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed