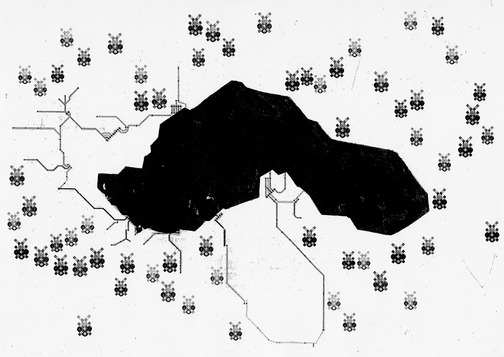

Clock of the Long Now prototype (CC piglicker) Clock of the Long Now prototype (CC piglicker) Originally published on the Time of Encounter blog, part of an AHRC funded project exploring social aspects of time. Fittingly, on the first day of the 14th Baktun, I want to continue with my focus on the Clock of the Long Now and the question of its ability to support a wider appreciation of deep time. For Brand, the “ambition and folly of the Clock..is to reframe human endeavour, and to do so not with a thesis but with a thing” (1999, 48). And so in this post, I want to focus, not so much on the theory of the clock, but more on the practicalities involved in actually building it, and particularly financing such a large and complex project. While the plan is to build multiple clocks around the world, the construction of the first clock is currently underway in West Texas on the property of Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos after he agreed to back the project to the tune of approximately $42 million. (You can find a great overview of the process from Dylan Tweney here). The site the Long Now Foundation had originally bought in Nevada is now being held in reserve for a second clock. Asked how he justifies spending such a large amount of money on a seemingly impractical project, Bezos told Wired’s Tweney that long-term thinking is just simply worth it, but also that ‘no other billionaire is building a clock like this, for the sole purpose of changing humanity’s relationship to time’. In much of the commentary on Bezos and the Clock of the Long Now there seems to be agreement that this is almost a match made in heaven. Bezos is well-known throughout the tech industry for being a long-term thinker. As he notes himself in an article for IEEE Spectrum his first letter [PDF] to Amazon.com shareholders in 1997 set out his interest in pursuing “long-term market leadership considerations rather than short-term profitability considerations”. His early investment in ebook readers is often cited as clear example of this priority of the long-term over the short. While the development of Amazon Web Services, and in particular the long-term online storage facility Glacier, could actually be seen to address some of the issues around short-term thinking in the tech world that Danny Hillis initially sought to respond to with his clock project (see my previous post). As Bezos has said in a number of contexts, one of the three basic rules of Amazon is “patience. We are looking at the long term. We know how to wait for results.” But what if we take a wider-view of clocks and the time of Amazon? In my first post, I suggested that understanding the role of time in social life would be helped by using a broader definition of the clock. Where a clock, is not an objective tool for measuring a single smooth flow of perpetual change, but as a device for social coordination, which was encoded with social values and produced through social decisions about what is important and what is not, what we need to be synchronised with and what we can ignore. What I want to suggest is that when we look at time in this way, the relationship between the Clock of the Long Now and Amazon doesn’t appear quite so felicitous. Fundamentally, while the Clock of the Long Now is trying to make long-term thinking automatic for those who experience it, the aim of Amazon is arguably to provide an experience of speed and immediacy. Each new innovation, from One-Click Ordering, Amazon Prime, the Kindle and even the long-term storage service provided by Glacier is guided by the desire to decrease the amount of patience asked of those who use its services. In conjunction with this we must also consider the high-pressure experiences of those working for the company itself and particularly the workers at the company’s fulfilment centres who must work at an extremely fast pace on short-term flexible contracts. If Bezos is serious about ‘changing humanity’s relationship to time’ shouldn’t he pay attention to the much wider changes his company is already facilitating? Can the Clock of the Long Now really compete with the Clock of Amazon?  Used under CC license Scottish Goverment Used under CC license Scottish Goverment How, for example, can its fulfilment centre workers think about the long-term when they have no security of contract? How can companies think about the long term, when Amazon claims that is Glacier service means that “customers no longer need to worry about how to plan and manage their archiving infrastructure”. While letting Amazon worry about the long term may sound attractive, as Brand and Hillis have claimed, many of their most interesting innovations have been produced through grappling with the concrete task of building the Clock. What Glacier does is allow the customer to lose the opportunity to learn more about the process of long-term thinking, as this can be outsourced to Amazon. More generally, Bezos’ focus on the customer’s experience centres on meeting the desire for a wide range of goods delivered fast at the cheapest price. But as Pheobe Sengers has suggested in her fascinating piece on time, technology and the pace of life, it is actually when you don’t have a great deal of choice, and can’t get things quickly that you start experiencing time in a more sustainable and relaxed way. What the Clock of Amazon allows is actually the ability to ignore the long term, to value immediacy and to act on fleeting impulses rather than make well thought out decisions. In Amazon’s defence, Brand writes in his book on the Clock of the Long Now that the project is not interested in slowing everything down. Instead he argues that it is actually the “combination of fast and slow components [that] makes the system resilient, along with the way the differently paced parts affect each other. Fast learns, slow remembers. Fast proposes, slow disposes. Fast is discontinuous, slow is continuous…Fast gets all our attention, slow has all the power. All durable dynamic systems have this sort of structure; it is what makes them adaptable and robust” (34). He suggests that commerce is one of the ‘fast’ systems of a culture, while other areas such as infrastructure and governance are slower and help moderate its excesses. From this point of view, perhaps the Clock of Amazon might not so problematic. Crucially, however, this rests on the assumption that governance structures are strong enough to shape businesses in particular ways and according to longer-term priorities. The reality seems to be further and further from the case. The consequences of paying poverty wages, of increasing inequalities between the poor and the rich and the repercussions of Amazon’s failure to contribute to broader social structures through its widespread tax avoidance are all long-term issues that Amazon is very clearly not being required to address. The idea of the Long Now came from Brian Eno, who after climbing over homeless people on a building’s steps in order to visit a glamorous loft owned by a celebrity, realised that for her ‘here’ stopped at her front door and ‘now’ meant this week (Brand 1999, 28). Shocked by the contrast between the poor and the rich he wrote that he wanted to be living in a ‘Big Here and a Long Now’. This is one of the fundamental ideas the Clock is based on. The risk in allying this understanding of the long-term with Bezos’ is that much of its radical nature could be lost, and the Clock of the Long Now could have very little chance of competing with the other ‘clock’ Bezos is also building. Reference Brand, Stewart. 1999. The Clock Of The Long Now: Time and Responsibility. New York: Basic Books  Clock of the Long now (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Piglicker) Clock of the Long now (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Piglicker) Originally published on the Time of Encounter blog, part of an AHRC funded project exploring social aspects of time. The Doomsday Clock and the 100 month clock both encourage a shift away from the idea that the future is something that automatically happens. Moving from a numbered time to one based on the qualities of that time, both suggest that unless we make significant changes in the present, there might not even be a future for the human race (and for most other life on this planet). In this post though, I want to look at the Clock of the Long Now, which offers quite a different perspective. Here the concern is not that we take the future for granted, but rather that we take no notice of it at all. So rather than having a clock that frames time within a twelve hour period, or a calender that frames time within a year, the Clock of the Long Now is being built to last for 10,000 years. First proposed by scientist and inventor Danny Hillis, this clock does not mark every second, or even every minute, instead it is one that “ticks once a year. The century hand advances once every 100 years, and the cuckoo comes out on the millennium”. This long sense of time is not (like the previous two clocks discussed) intended to produce a sense of the devastating consequences of our current way of life, but instead, to start to imagine what could be accomplished over long periods of time with continued effort. The concern with taking a longer view was partly to counteract the very short term thinking that Hillis noticed within I.T. projects. For example, when a very early computer was shut down at M.I.T. all the information had to be moved to magnetic tapes which can no longer be read. This meant that “we lost the world’s first text editor, the first vision and language programs, and the early correspondence of the founders of artificial intelligence” (Brand 1999, 84). As Steward Brand, another co-founder of the project commented, “science historians can read Galileo’s technical correspondence from the 1590s but not Marvin Minsky’s from the 1960s”. In starting to think through the design problems involved with building a device that would last for 10,000 years, it’s interesting that Hillis’ awareness of the ability for low tech methods to last, where high tech fails, has meant that the progressive narrative of a continuously technologically advancing future had to be seriously questioned. Instead, when you have to think about the future in much more specific ways, e.g. how to make a particular physical device operate for an extended length of time, the unknowability of the future becomes much more pronounced. Instead of trusting that things will always improve, as so many ‘return to growth’ advocates do, the desire to make something last actually seems to bring out a more cautious approach (see also “Into Eternity”). Not knowing what the future held meant that the key design principles had to be based on the idea that people in the future might not have the knowledge or the materials to deal with a device built using our current technology. So the clock had to be able to be maintained using technologies available during the Bronze age, but also had to be ‘transparent’. That is, the clock mechanisms should be able to be figured out by an intelligent person only by observing the mechanism itself.  Mechanism on prototype (CC BY-NC 2.0 Madichan) Mechanism on prototype (CC BY-NC 2.0 Madichan) Hillis’ interest in Bronze Age technology was criticised by futurists who understood the clock as a reversion to the past, rather than showing us the future. This in itself is interesting since it shows quite clearly how inbuilt the assumption of progress is, even with those who devote their careers to thinking about time and the future. A further question they posed though is more interesting. According to Po Bronson, “in their opinion, by demonstrating the technology of the past, the clock will make us think about the past”. That is, in the future will the clock still make people think of the times ahead or would it instead make people think more “about what life was like in 2000, and wonder why in the world someone way back then would build such a thing.” But perhaps the focus on whether the clock tells us about the past or the future is to slightly miss the point, since these criticisms still use a framework of time-as-we-know-it. That is, the conception of time being drawn on in the criticisms has not itself been called into question. The Clock of the Long Now is not necessarily telling ‘our time’ rather it is trying to connect us up with ‘deep time’, arguably a fundamentally different kind of time. Can progress and regress really mean the same thing when thought about in the context of tens or hundreds of thousands of years? More importantly does it matter if people in the year 4000 (or 04000) are thinking about us in the 2000s rather than those in 6000s? It seems that one of the key points of the clock is that the kinds of relations produced by a standard clock, where we are often only thinking about those close in time to ourselves, are transformed. The triumph will be if people divided from each other by millennia are thinking about each other at all… Reference Brand, Stewart. 2000. The Clock Of The Long Now: Time and Responsibility. New York: Basic Books. Sounding Drawing is one of the three projects that make up the Time of the Clock, Time of Encounter project and was led by Anne Douglas, Kathleen Coessens, Mark Hope and Chris Freemantle (On the Edge (OTE) Research, Woodend Barn Arts Centre, Orpheus Research Centre in Music (ORCiM), Champ’D’Action, and Ecoarts Scotland). It involved a practice-led experimentation in and improvisation around linking sound and image. In the second workshop participants were asked to create a 'score' for a drawing. The groups came together almost by chance or instinct and I found myself in a group with Fiona Hope and Isaac Barnes where we collaborated on 'sounding' Ann Eysermans P6. You can hear the results just below. |

Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed