|

Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy?  The Grey Gentlemen from Michael Ende's "Momo", as a grafitti on a wall in Trier. (Sebastian Nebel CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) The Grey Gentlemen from Michael Ende's "Momo", as a grafitti on a wall in Trier. (Sebastian Nebel CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) This project tackles not one, but two amazingly complex issues - time and economies - and so as part of setting up the project I’ve had meetings with each of the advisers and project partners to get a better idea of the kinds of issues they think it would be important for the project to address. It’s been fascinating talking to everybody one-on-one and to start unpacking how we might go about researching the question of time and sustainable economies. A range of themes came up in our discussions, but the most prominent was around the relationship between time, money and value. Arguably one of the key moves made by capitalist economies has been to turn the time of our lives into abstract units of time that can then be sold in exchange for money. One effect of this is that time not spent earning money is devalued. A quick look at the nef report 21 Hours: Why a shorter working week can help us all to flourish in the 21st century reveals a wide variety of examples of this, including a critique of the failure to value care work (which is often unpaid or low paid) adequately. So in thinking about what kinds of case studies we want to develop, one key area will be exploring how people are unpicking the relationship between time, value and money and reknitting it in different kinds of ways. People practising voluntary simplicity, for example, will probably have lots of insights into this since the emphasis there is on reducing your need for money as part of valuing time more. Craftspeople, artists and those engaged in self-provisioning work (food-growing and preserving for example) also regularly confront the mismatch between the value and quality of their work, their experience of time and the kinds of monetary returns they can expect. What kinds of practices have people developed to decommodify their labour and to experience their time as intrinsically valuable? Another issue that came up turns our original question on its head. So rather than asking what kind of times are the new economics creating, people were also interested in what kind of time is needed to even engage in trying to do economies differently. There can be a tendency to assume that everyone can be involved in this, but the same kinds of opportunities aren’t available to all. Time poverty and low incomes restrict how people can get involved. So we’re also interested in how the ‘opportune moment’ opens up for people to take the leap into doing things differently. When does this happen? At what stage in people’s lives? And with what support systems in place? Importantly how do people negotiate the kinds of compromises they might be required to make in order to open up time for change, or to keep the new project moving along? More specific issues related to an interest in whether the frameworks already in place around the co-operative and permaculture movements might have anything in particular to tell us about sustainable times. Chris Warburton-Brown, for example, suggested that if time is a resource, and permaculture is about designing more sustainable resource-use, then perhaps those practising it will already have important insights that the project can learn from. He also suggested it would be interesting to explore what kinds of time have already been assumed by the philosophical basis of permaculture. Issues to do with the role of the past and the future were also important. How might the seven principles of the original co-operative founders developed in the 1800s address issues that new co-ops are facing today? More generally, an important question arising from our interest in ‘thinking forward through the past’ will be how can we inherit from past experiments with alternative economies without being overly nostalgic or romantic? Alternatively, if capitalism has been widely characterised as blighted with short-time horizons is it the case that alternative enterprises are developing a more extended sense of past and future? Does the idea of being accountable to the next seven generations, for example, resonate with the people we will be visiting and working with? Finally, our discussions also brought up issues of social and environmental change. Time is important here because our understandings of how change happens and what counts as a change are shaped by our conceptions of time. A linear model of time suggests that change happens when an individual decides the result they want and puts in place the incremental steps needed to achieve that result. A more complex model of time questions our ability to predetermine results in this kind of way. Here in particular Debbie Bird Rose and I talked about the contrasts between an ecological time where very slow processes can be combined with feedback loops and sudden shifts between states, and human (often bureaucratic) accounts of change which depend on ideas of stability and predictability. Might a more sustainable understanding of time respond better to the ‘patchiness of change’ which we see in climate data for example? Molly Scott-Cato also raised the issue of how to combine ideas of dynamic change with a need to be fixed within limits. Within capitalism dynamism is linked with growth, but in the arts, for example, creativity and limits can go hand in hand. An important issue here then is challenging the idea that nature provides a timeless and unchanging backdrop to a progressive and inventive human economy. Suggested case studies to explore this topic include working with communities that are experiencing nature as an active and abrupt force in their lives (e.g. through floods, severe weather etc) and what kinds of mechanisms they are using to deal with this, but particularly exploring whether these experiences are challenging people’s understandings of time. Alex and I are off to the Co-op archives next week to see what we find there so stay tuned! Originally published on the More-than-Human Participatory Research blog, an AHRC funded project exploring the possibility of extending participatory research techniques to non-humans.  Our first workshop is coming up soon and Clara Mancini and I have been having some really fascinating discussions about how to actually organise it. For this workshop we'll be working with dogs and people from Dogs for the Disabled who have generously agreed to participate. We're going to explore how to utilise methods from participatory design to invite the dogs into collaborative research processes. One definition for participatory design from wikipedia suggests that it is a process where participants: are invited to cooperate with designers, researchers and developers during an innovation process. Potentially, they participate during several stages of an innovation process: they participate during the initial exploration and problem definition, both to help define the problem and to focus ideas for solution, and during development, they help evaluate proposed solutions. Assistance dogs use a variety of objects designed for humans as part of their work. This includes things like door handles and light switches, but also more complicated things like washing machines. One dog in New Zealand had even learnt how to drive a car. These items can be adjusted for dogs to use, by adding a rope to a door handle, for example, but what if you could use methods from participatory design to create interfaces specifically for dogs? As Clara said today in our discussions, to design with someone (whether this be human or non-human) means coming to a stage where you've recognised that someone as worth catering for, as somebody that has requirements of their own. To design with and for dogs is to also recognise that they are worthy recipients of technology. What we are hoping to do then is to use our workshop as an opportunity to do a test run of a participatory design process with dogs. We will pilot methods of doing an initial exploration and problem definition on the first day, by learning about the kind of relationship that exists between users and the dogs. We'll then focus on how the dogs learn their tasks and in particular how they learn to interact with the different technologies that they use. We'll look for issues, difficulties or complications that arise, as part of defining problems that may need a design solution. On day two we are then planning to work in groups to develop responses to design briefs arising from our problem definition work from the day before. We're hoping to explore how we could support better communication and recognitions of agency through technology designs. Addressing issues around usability, functionality and aesthetics, we are hoping to touch on questions on how to think through the value of design for different species. Given how short our workshop is, we won't have time to test out evaluation methods, but we'll be hearing about some methods that the ACI team have being developing. It's all feeling quite experimental at the moment, and is proving to be both challenging and fascinating. Stay tuned for updates on how it ends up playing out. Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy? Written by Alex Buchanan (University of Liverpool)  mystuart (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) mystuart (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) In our previous post, we described some of the changes in the baking industry following the deregulation of bread prices in the UK in 1815. In this post we wanted to outline some of the temporal dimensions specific to baking that have been revealed in our preliminary research: Night-working. Long hours worked at night were the main factor that set baking apart from other crafts. Night working was promoted both by the consumer (wanting to purchase fresh bread before work in the morning) and the supplier (the journeyman working on commission, who needed to buy the amount of flour agreed with the miller or corn factor). The introduction of the free market encouraged longer hours and during the nineteenth century, bakers might have only 4-5 hours sleep each day. Yeast - bread-making was a lengthy process, needing to take into account the cycles of rising and kneading. Until the production of dried yeast, it needed to be nurtured as a living product, in the forms of barm or ferment - which remains true of traditional sourdough bread. In 1859 the aerated bread process, which needed no yeast, was patented by Dr John Daulish, founder of The Aerated Bread Company. This reduced the length of time taken in breadmaking from around 10 hours per loaf to around 2 - but the high costs of the machinery limited its take-up. Perishability - this limited bread production to the locality and required consumers to make regular purchases. In a fascinating article on the Halifax (Canada) baking and confectionary industry, we found a quotation from an 1868 petition by the Journeyman Bakers' Friendly Society "To the Master Bakers of Halifax", which puts the workers' hours of labour into a social and moral context designed to resonate with public opinion on respectability. In a moral and intellectual point of view it is nearly as bad, as we have no time for recreation, no moral improvement; no time to spend in the social or family circle. We have no time for the public meeting, lecture, concert or religious duty; the Sun shines in vain for us, the trees and plants may grow, and the flowers may bloom, but not for us. To us the delights of the country are a sealed book; to prepare for our early toil we have to go to bed, (those that have one), while the rest of the world is awake, and work while the rest of the world asleep, thus reversing the laws of nature. No wonder that some of us have recourse to stimulants in order to give a spur to our overworked and failing nature, and for the time to bury in oblivion our degraded position.' Modern breadmaking methods have reduced the need for night working, by cooling dough down to low temperatures - its fermentation is then halted until it is warmed up again. Modern methods, including par-baking and the use of steam ovens, have even enabled bread to be transferred directly from freezer to oven. The use of frozen dough has allowed for the introduction of on-site baking and the continuous supply of fresh bread in supermarkets etc. The return to artisan baking, however, means that some of the time conflicts experiences by bakers in the 1800s are being re-visited today. We’ll explore this in our next post.

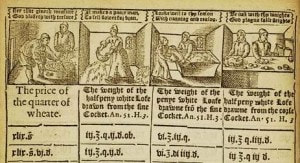

References: Burnett, J., 'The Baking Industry in the Nineteenth Century', Business History, 5/2 (1963), pp.98-108 Collins, E.J.T., 'Food adulteration and food safety in Britain in the 19th and early 20th centuries', Food Policy, 18/2 (1993), pp.95-109 Decock, P. and S. Cappelle, 'Bread technology and sourdough technology', Trends in Food Science & Technology, 16/1-3 (2005), pp.113-20 Gourvish, T.R., 'A Note on Bread Prices in London and Glasgow, 1788-1815', The Journal of Economic History, 30/4 (1970), pp.854-60 McKay, I., 'Capital and Labour in the Halifax Baking and Confectionary Industry during the last half of the Nineteenth Century', Labour/Le Travail, 3 (1978), pp.63-108 Ross, A.S.C., 'The Assize of Bread', The Economic History Review, 9/2 (1956), pp.332-42 Stern, W.M., 'The Bread Crisis in Britain, 1795-6', Economica, n.s. 31/122 (1964), pp.168-87 University of Durham, Special Collections and Archives, 'Bread through the Ages', available at http://www.dur.ac.uk/~dul0www3/asc/bread/control1.htm Webb, S. and B., 'The Assize of Bread', The Economic Journal, 14 (1904), pp.196-218 Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy? This post was written by Alex Buchanan (University of Liverpool) For many people the new economics is synonymous with the rise of the artisan economy. One of the flagships for this movement is the revival of artisan bread, which includes the rise of community bakeries, such as Homebaked Anfield and the campaign for Real Bread. In order to start to tease out the relationships between time and alternative economies we’ll be including case studies of a variety of new artisan businesses. However, we’ve also been really interested in the way many approaches to the new economics explicitly draw on the past for inspiration. So we will also be exploring how archive research might shed light on contemporary questions about economics and time. We’ve been doing some preliminary research into what kinds of records might give insights into baking methods and cultures. Part of this involved finding out more about the history of the baking industry, to identify what records might have been created. This research has already thrown up some interesting findings which relate to the time-dimension and economics of baking.  Woodcut showing the making of bread in bakeries, from The Assize of Bread 1608 Woodcut showing the making of bread in bakeries, from The Assize of Bread 1608 Until 1815, bread-making was controlled by medieval legislation: the 'Assize of Bread' of 1266. This stipulated the size, weight and price of loaves according to the price of wheat and included other regulations for bread production. A number of books listing sizes and prices of loaves survive: we looked at one in the Liverpool University Special Collections as part of the 'Memories of Mr Seel's Garden' project; there's another one online here. The Assize did not prevent price fluctuation, but linked it to the grain market. Rather than competing against price as we do now, under this system, competition between bakers was based on bread quality, as it was illegal to produce cheaper loaves. This ideally led to better tasting bread, rather than simply cheaper bread. Although in times when flour was expensive, adulteration was common. During the eighteenth century, however, the monopoly of the craft guilds was breaking down and increasing numbers of bakers (often not master bakers, but journeymen acting as agents for millers and flour merchants) began to undercut the fixed price - and were hailed as the champions of liberty against the bastions of ancient privilege. After the end of the bread crisis and famine years of the late 1790s, many towns abandoned the Assize and a Parliamentary Committee appointed to enquiry into the matter in 1815 recommended that more benefits were likely to be incurred from free competition.

The actual results of deregulation, however, were revealed by H.S. Tremenheere's 1862 Report Addressed to Her Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for the Home Department, relative to the Grievances complained of by Journeymen Bakers, with Appendix of Evidence, 3027, H.C. (1862). This documented an industry still dominated by artisan methods but in appalling conditions and for low financial reward, with prices kept down by low wages and adulteration. In particular, alum was added to flour to meet public demand for 'white' bread - perceived as being purer and therefore of higher quality. Under these circumstances, author John Burnett, writing in 1963, viewed the introduction of technology and changes brought by improved scientific understanding of the baking process, as well as the importation of grain from further afield, as advances which 'rescued the journeymen from the miseries of 1862'. We’ve found a number of interesting transformations in senses of time occurring during the process of deregulation, which we will outline in our next post. Alex Buchanan  I'm pleased to say that I've finished the write up for the final event from the AHRC- funded Temporal Belongings follow on project which has explored the links between time and community. The workshop was held on the 17-18th January 2013 and its focus was Power, Time and Agency: Exploring the role of critical temporalities. Listen to a wide range of talks from the conference, including keynote speakers Lisa Adkins and Jane Elliott, and see some of the results from our collaborative sessions here |

Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed