|

Ever since reading Thoreau as a child, and his arguments against spending our time working to buy things we don't always need I've been interested in work, time and finding your own 'enough'. As a result it was a pleasure to talk with Samuel Alexander, founder of the Simplicity Institute about the how our conceptions and experiences of time play a role in moving towards less consumption based lifestyles. We talk here about everyday time use, but also ideas of progress, success and revaluing time.

Tamara DiMattina is a social entrepreneur who has been involved in a number of sustainability projects focusing on reducing consumption. We were intrigued by her project 'Buy Nothing New Month' with its clear objective of using time as a basis for reforming our relationship with 'stuff' and so conducted this interview with her about the project. We talk about time, fashion, creativity and whether or not sourcing things second hand might actually give you more time.

Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy?  Slow food this way (Laurie O'Neill CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) Slow food this way (Laurie O'Neill CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) The Slow Movement often comes up when I talk to people about the Sustaining Time project. It’s a nice clear way of explaining why you might want to think about time as part of developing more sustainable forms of economics. Slow Food, for example, suggests that a sustainable food system would need to use a very different time to the one guiding industrial agriculture. And of course the slow movement hasn’t stopped there but has been moving into a whole range of different areas, including into research with ‘slow science’ and ‘slow scholarship’ gaining more attention. So I have very much been looking forward to attending the Slow University II seminar, which was held in Durham last week, and included Carl Honoré and Chris Watson as speakers. It seemed like a great opportunity to explore the 'sustaining time of research'. But throughout the event, I found myself becoming increasingly uneasy about the way the Slow ethos was being deployed, particularly in Carl's presentation, and I wanted to explore some of the reasons here. Carl Honoré has been writing about the Slow Movement for some time now and many people at the event had brought along their copy of In Praise of Slow. His presentation covered similar themes to this book, including his own epiphany over needing to slow down when he realised he was constantly rushing through story-time with his son. He also explored a number of examples of the way the slow ethos is showing up in the most unlikely of places including Google’s 20 percent time project, Ariana Huffington’s effort to redefine success with the Third Metric and Jeff Bezos instituting 30 minutes of silent reading before meetings at Amazon. If these businesses could recognise the benefits of Slow why not the university? And so Carl offered three suggestions for what proponent’s of a Slow University might want to focus on:

Amazon - Official Opening (CC BY-NC 2.0 Scottish Government) Amazon - Official Opening (CC BY-NC 2.0 Scottish Government) The question of who is Slow for? was asked in a couple of reflections on the first Slow University seminar and, I think, continued to be a prominent question at this event. It is a crucial question, because as Sarah Sharma argues in her recent book In the Meantime: Temporality and Cultural Politics “capital invests in certain temporalities - that is, capital caters to the clock that meters the life and lifestyle of some of its workers and consumers. The others are left to recalibrate themselves to serve the dominant temporality” (139). In each of the three large organisations mentioned above, for example, it is very clear that Slow is only for some. As Andrew Norman Wilson’s contribution to FACT’s Time & Motion exhibition uncovers, Google’s used of colour-coded badges determines how much access an employee has to self-directed work time and its time-saving infrastructure of free shuttle buses, meals, haircuts etc. Ariana Huffington has come under regular criticism for her business model based on the free labour of others, including masseurs. And even Carl noted the hellish conditions suffered by workers in Amazon’s ‘fulfilment centres’ (see also my post on the time of Amazon). When I asked about these discrepancies in the implementation of the slow ethos, Carl suggested that the model could be seen as a kind of Trojan horse that has the ability to transform organisations from the inside once it has found an initial foothold. Perhaps he will be proven to be correct, but part of me wondered whether it might not be the other way around. Was neo-liberal capitalism instead turning slow to its own ends, adding slow-washing to its stable of methods that already included green and white-washing? The benefits of Slow were almost completely described in terms of its ability to make you a better worker. Far from being ‘the opposite of a productivity ninja’ as was suggested at the beginning of the seminar, 'slow' seemed to equal 'productive'. For example, Carl talked about the ‘delicious paradox of slow’ where working slow actually allowed you to work faster, producing more than someone caught in a harried, unfocused rush. Described in this way it didn’t seem that the ethos of Slow was operating as a critique of capitalist temporalities of production but might instead be one of its latest incarnations. A core aim for the seminar was to find ways of supporting ‘ethical scholarship for the common good’ through recalibrating the time of the academy. But the focus on individualised experiences of speed and pressure, which seem to dominate the literature on the Slow ethos, suggest that it might have capitulated too easily to what Sharma describes as the “expectation that everyone must become an entrepreneur of time control” (138), where we invent and implement our individualised techniques of slowing down. Such an approach fails to deal with the uneven and unequal ways our time is intertwined with others and thus to confront the “new forms of vulnerability [that] are necessitated by the production of temporal novelties or resistances to speed” (150). Perhaps the core question then isn’t how can the university slow down, but how might it find ways of supporting ‘ethical times for the common good’. Reference: Sharma, Sarah. In the Meantime: Temporality and Cultural Politics. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2014. Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy?  Economics by Mark Wainwright (CC BY 2.0) Economics by Mark Wainwright (CC BY 2.0) It’s been a little while now since we’ve put up a new post on this project and I can’t help but feel the irony of not having enough time to devote to a project that is exploring the possibility of developing more sustainable relationships to time. But as perhaps many others have found, your projects never really forget about you. They keep calling to you, cutting through all your busyness and eventually reeling you back in. So to get back into the swing of things, I wanted to revisit some of the core questions that first inspired the project. Starting off with the most obvious perhaps: Why might a focus on time be important for understanding how to shift to more sustainable economies? The perfect storm of multiple crises, including climate change, the peaking in supply of a whole range of key resources, as well as the astounding inequality fostered by current economic systems, have turned many towards developing and implementing alternative approaches. Challenging the philosophical basis of conventional economic theories has been an explicit aspect of this. As a result, the dominant paradigms of neoclassical economics are, at best, seen as being comprised of naive assumptions that fail to capture the complexity of human interdependencies on each other and on the environment. All around us, the dominant stories of how people interact with each other and the kinds of incentives and rewards they respond to are shifting. Instead of competitive self-interested units, we are more generous, more co-operative and more complex than main-stream economists give us credit for. The structure and characteristics of the web woven between the human and non-human, between the biological, the mineral and the elemental are being questioned and described in new ways. Gift-based economies, the new commons, cooperation, abundance instead of scarcity and distributed networks are just a few examples.  Bestwood factory entrance by Sludge G (CC BY-SA 2.0) Bestwood factory entrance by Sludge G (CC BY-SA 2.0) How might time fit into this then? If time is just an objective flow that we measure, then it has about as much to do with economics as π (pi) does. It’s an unchangeable constant that we just need to live with. But what if this story about time is as much of a distortion as the story about ‘economic man’? What if time is also more complex, more interconnected and more dependent on social webs than we’re usually taught? That like the maps that tell us stories about space, our clocks are not simply telling us ‘the time’ but are telling stories about time that are cultural, political and partial? What if time is tied to our webs of relations in such a way that when these webs change so does time? There is already research that suggests that broadly speaking different economic systems seem to be associated with different approaches to time. For example, pre-industrial societies with task oriented time, industrial capitalism with an intensification of clock-time and late capitalism with speed and acceleration. And if we look for further clues within alternative economics, new sustainable times come tantalisingly into view. Steady-state futures or degrowth displace stories of the progressive arrow of time. Movements like Slow Food, Permaculture or Transition are making deliberate attempts to redesign everyday life around slower tempos and complexity-based models of social change. This suggests that social change doesn’t only happen in time, but happens through changes to time itself. The aim of this project then is try see if we can make some of these shifts in time more visible and more intelligible. But in going about this, we are making the following assumptions which make things more complicated:

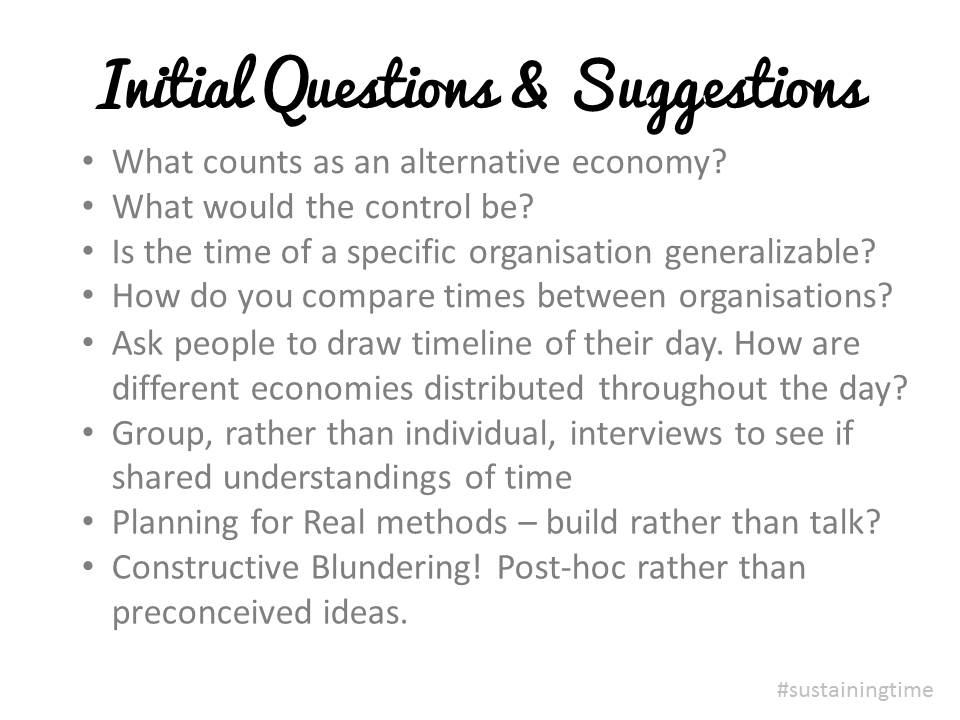

Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy? A key question for us since we first started thinking about this project, was not only what is the time of sustainable economies, but how we might find it. How on earth do you actually go about researching people's perceptions of time? As anthropologist Kevin Birth writes eloquently in his paper Finding Time: Studying the Concepts of Time Used in Daily Life: Cultural conceptions of time do not lie by the side of the road waiting for an ethnographer to wander by and pick them up. Indeed, the idea of the naïve fieldworker walking up to some beleaguered informant and asking, “What are your cultural ideas of time?” is amusing in its absurdity. There is something about time that makes it seem extremely important to understanding how people live, yet it seems an intangible concept. It seemed to us that the project provided a great chance to address a series of interesting methodological questions. Work that has come out of the AHRC Connected Communities theme, for example, has raised a number of questions about the ability of established research methods to do justice to the dynamic nature of communities (see particularly McLeod & Thomson 2009; Law 2004; Abbott 2001). They suggest that need to understand communities as being in time, (or even as producers of time), just as much as the more usual focus on communities and space, territory, locality etc. We were also intrigued by the development of methods for researching experiences of space as changing and dynamic, which have been coming out of the mobilities research paradigm (Buscher, Urry, Witchger 2011). What methods might researchers use to study the way time itself can also be changing and dynamic, rather than simply assuming that time provides a taken-for-granted background to everyday life? Since the remit of this project was, above all, to be exploratory, we created a variety of opportunities for us to reflect on methods as the project progressed. We asked for advice from our Project Partners and Advisers and I've summarised their suggestions in the slide below: In some ways the approaches we have been using are perhaps on the more conservative side, in that we are focusing primarily on archival research, participant observation and open-ended focus group interviews. Even so we've been finding that attempting to use these methods to research the slippery subject of time has ended up working back on the methods themselves. You can read about Alex's experiences in the archives here and here, for example, and we'll be adding further reflections as we go along.

But given that we were also aware that there are a wide variety of other methods that have been developed, we were excited to be able to include a Methods Festival for Studying Perceptions of Time, which took place on the 26th of June 2013. Organised by Jen Southern, this event explored the potential of arts, design and technology practices for researching shifting temporal paradigms, as well as a number of different ways that social science methods have been put to use in studying time. The talks from this event are now online and can be accessed here. References Abbott, A. (2001). Time Matters: On Theory and Method. Chicago, University of Chicago Press. Birth, K. (2004). "Finding Time: Studying the Concepts of Time Used in Daily life." Field Methods 16(1): 70-84. Bryson, V. (2008). "Time-Use Studies: a potentially feminist tool?" International Journal of Feminist Politics 10(2): 135-153. Büscher, M., J. Urry, et al., Eds. (2010). Mobile Methods. Abingdon, Routledge. Law, J. (2009). After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. Abingdon, Routledge. McLeod, J. and R. Thomson (2009). Researching Social Change: Qualitative Approaches. London, SAGE. Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy? Written by Alex Buchanan (University of LIverpool) The Sustaining Time project is funded under the AHRC's Care for the Future theme. In keeping with its aim of 'thinking forward through the past', one strand of our project is scoping out the potential of archive resources to provide material for understanding how alternative economic models might challenge dominant approaches to time. The team will be visiting four archives over the course of the project. This post by Alex Buchanan is the second in a series that looks at how we've approached the task of finding time in the archives.  The Working Class Movement Library by Andrew Nić-Pawełek (CC BY-SA 2.0) The Working Class Movement Library by Andrew Nić-Pawełek (CC BY-SA 2.0) My most recent archive visit was to the truly inspiring Working Class Movement Library (WCML) in Salford. The WCML was established as a labour of love by Eddie and Ruth Frow, lifelong members of the Communist Party, who dedicated their leisure time to collecting books, archives and memorabilia recording over 200 years of working class history. When the collection outgrew the Frows’ own house, it was moved to the present location, a Victorian former nurses’ home in Salford Crescent. It has received a number of grants, notably from the Heritage Lottery Fund, to ensure that the collections are catalogued and accessible – an ongoing task managed by both a professional staff and an enthusiastic team of volunteers, of which Ruth Frow was a member until her death in 2008. The enthusiasm of the Frows – and their supporters – for working-class history is in itself reflective of an attitude to time which demands the memorialisation of historical events – and the people involved, whether or not their names survive – in order that they may inform and inspire those who follow in their footsteps. Marx’s work, deeply informed by his understanding of history, ensured that his followers have been equally keen to trace the seeds of historical change, which might document the potential for revolution. Thus the collection in itself is a document of a particular temporal awareness, which is also obviously present within its contents. A single example will suffice: a booklet printed as part of the celebration of the Dorsetshire Labourers’ Centenary in 1934. This event, staged in collaboration with the Trades Union Congress, commemorated the Tolpuddle Martyrs, the Dorset farmworkers sentenced to transportation to Australia as convicts for joining together as a union in 1834. The centenary involved a number of activities designed to raise awareness of the historical dimensions of trade unionism, including an elaborate series of tableaux telling the story of events in Tolpuddle. In the words of Labour M.P. Arthur Greenword, quoted in an advertisement for the Co-operative Printing Society Ltd (printers of the leaflet): 'What we as workers have lacked, is tradition, and now we are building it.’  Charles Bedaux with filmmakers Charles Bedaux with filmmakers Thanks to the useful catalogue and the knowledgeable guidance of former librarian Alain Kahan (for which I am extremely grateful), I identified a number of other useful resources which will repay further study and a number of record types and historical episodes which we can try to explore in the collections of other repositories. In scoping the ‘Sustaining Time’ project, we identified that useful archive material was likely to be generated as a result of industrial disputes – and this proved very much the case at the WCML. Two particular themes emerged: industrial workers’ concerns about new ‘scientific’ management techniques which involved time and motion studies, and ‘white collar’ unions’ concerns about ‘flexi-time’, that is to say working practices involving changes to working hours. In terms of management, business historians have already identified that in the UK, neither the so-called scientific techniques of the famous Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915), nor the production-line management of his fellow American, Henry Ford (1863-1947), were as directly influential as the approach of Charles Bedaux (1886-1944), whose management consultancy business had a branch in London. Much research has been devoted to charting the spread of modern management in the UK and numerous firms, including Vickers Instruments, Rover cars and ICI have been shown to have adopted Bedaux methods. Other firms are known to have overhauled their processes without employing efficiency engineers – the new approach soon became an essential tool of modern management. What is particularly fascinating about the WCML’s collections is that they provide a glimpse into the other side of the picture – the reaction of the workers to these new methods of control, which extended to the imposition of particular bodily actions in order to increase efficiency (and reduce fatigue). In the archive is a file of legal papers drawn up as part of a dispute between members of the Wiredrawers’ Union and Richard Johnson and Nephew, of Bradford, Manchester in the 1930s. These provide an insight into the workers’ objections, which focused in particular on their unease at the use of stopwatches to time workers’ actions. This was felt to be an attack on the industrial expertise and autonomy of the employees, who valued their identity as highly skilled craftsmen. Sadly for them, their long strike did not achieve its aims of rejecting Bedaux, nor were the strikers eventually reinstated – however they received much local and national support and much publicity for their cause. My next archival trip will be to the Modern Records Centre at Warwick University, where I expect to find more information about opposition to the Bedaux system and other worker campaigns over attempts to control their temporal autonomy. Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy? The Sustaining Time project is funded under the AHRC's Care for the Future theme. In keeping with its aim of 'thinking forward through the past', one strand of our project will scope out the potential of archive resources to provide material for understanding how alternative economic models might challenge dominant approaches to time. The team will be visiting four archives over the course of the project. This post by Alex Buchanan is the first in a series that looks at how we've approached the task of finding time in the archives.  Our first archive visit was to the National Co-operative Archive. This was a great place to start our research, in part because of the way the archivists have helped to make their resources accessible. As I'll explain in this post, the level of detail used in the archive descriptions enabled us easily to identify items which might be of interest and to order them from storage before we arrived. This won't be the case at other archives we visit, so I'm going to use this post to explore how archivists' work can support research, whilst recognizing that such efforts aren't always possible. Since the nature of our research is so specific, i.e. finding out how those experimenting with economic systems might be thinking about time, we will have to put in some additional effort to understanding both the domain and the archives we use in order to get the most out of these resources. There are 6 ways of searching the Co-op archive online, including an image search, which we did not use. In line with most users' preferences, the default option is a simple free text search. We used this to identify the majority of the items we used, by using keywords including: time, hour/s, work, working, clock/s, future, nature, change, evolution, progress, history, environment, flood/s, earthquake/s, disaster/s. However, as our list of search terms suggests, the disadvantage of this method is that even changing the word from singular to plural brings a different list of results, because the search engine simply looks for exact matches anywhere in a description. This creates a number of problems when trying to research time in the archives. A good example was our search for 'clocks'. Anyone looking for clocks may also be interested in watches, but because the word has another, more common meaning this can confuse the results. In our case, all the item descriptions that included the word 'watch' were for images involving onlookers. This means that it is possible that the Co-op archives include information about pocket and wrist watches (these were often retirement gifts for long serving employees in many businesses, for example), but unless the archivist has included the word in the item description it will not be accessible via a keyword search. One of the ways archivists try to deal with this and other problems associated with keyword searching is to 'index' archives - that is to say, to associate the description with a number of 'authority terms' which the cataloguer decides have particular relevance for the unit being described. At the Co-op archive there are indexes for names (of people and organizations), subjects and places. Authority terms are created as a separate exercise and can involve considerable research, to ensure that, for example (and, not, as far as I am aware, featuring in the Co-op Archive), Robert Smith, equestrian, son of Harvey Smith, is not confused with Robert Smith, musician, lead singer in The Cure. When used consistently, indexes can often be the most efficient and effective means of searching - but they are labour intensive to create. Of the three types of index, subject indexes are perhaps the most problematic for archives. From the point of view of an archivist, archives are not in the first instance information resources because - unlike books - this is not the purpose for which most records were created. Most records are created as evidence - to provide a persistent representation of a time-delimited event. Minutes from meetings provide a good example of this. As the influential archival writer Sir Hilary Jenkinson (1882-1961) declared, they 'were not drawn up in the interest of, or for the information, of posterity'. The American archival theorist T.R. Schellenberg modified this perspective, by suggesting that archives have two sets of values: primary values for their creators and secondary values for other users, which come into play in particular when records, created for current purposes, cross the 'archival threshold' and then may be used by a wide variety of users for a wide variety of purposes. Archivists want to open the records in their custody to the widest variety of users and uses. Subject indexing is intended to assist with this but archivists cannot predict all the possible topics future researchers may want to investigate. Trying to represent the subject matter of a document from the perspective of its creator/s follows archival theory's traditional emphasis on provenance (discussed further below) and thus appears theoretically straightforward, although it inevitably involves difficult decisions in practice, as anyone who has ever tried to describe a photograph without knowing what the photographer was trying to capture will recognize. Extending this indexing to include possible research topics is fraught with difficulties and is thus rarely attempted: a more common approach is the 'Subject Guide', whereby an archivist gathers together potential resources for a researcher interested in a particular subject area. However, when embarking on this research, we were aware that the elusive nature of time and temporal awareness was one of the difficulties we would have to overcome (which will be explored in our 'Methods Festival' in June) - there are no useful archive guides on temporal research to assist us. Archivists' descriptions try to represent the context of creation of the records - this is what is known as 'provenance'. Whilst archives can be used to support an almost infinite variety of research topics, which will inevitably change over time, it is generally accepted that our understanding of the people and processes that created the records in the first place are likely to remain relatively constant and that this knowledge is vital for interpreting the records' historical meaning. This means that archivists try to maintain the original order of the records, and list them according to their creators. Thus at the Co-operative Archive, all the records of the Crumpsall Biscuit Works are described as a single group. They are, of course, not all the records created - the vast majority have not survived, but enough remained for us to get a sense of the importance the Co-op movement accorded both to worker welfare and to production efficiency in this model factory. In an archive where descriptions are less full than at the Co-op, the only way we may be able to identify records relevant to our research will be by identifying the types of organizations and the historical circumstances which might produce records of potential interest. Again, by starting with an archive with a very detailed catalogue, we have started to build up a picture of what sorts of series of records are likely to be of particular significance to our research. In a later post, I'll explore how 'Time' is represented in other forms of resource discovery, such as library catalogues. Alex Buchanan Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy? This post is written by Chris Warburton-Brown  Rush Hour by Tuan Minh Pham Rush Hour by Tuan Minh Pham Chris Warburton-Brown is the Research Coordinator at The Permaculture Association and in this post he explains why Permaculture UK got involved in the Sustaining Time project. Wasting time, spending time, giving you my time, running out of time, investing time, in your own time... all of these common phrases suggest that we see time as a finite, own-able resource like any other. And it would be fair to say that most of us feel that resource is often in short supply in our lives as we try to reconcile the demands of work, family and leisure. But unlike other finite resources that are in short supply in post-industrial society, most of us in the environmental movement have not yet formulated much response to the shortage of time we often experience. This is all the more strange when we realise that our relationship to time as a finite resource is intimately linked to our relationship to other finite resources; oil to fuel rapid transport, electricity to power labour saving (i.e. time saving) domestic devices, farmland or forest lost to build road, rail and airport infrastructure. The slow food movement has made these connections and recognised that locally grown and cooked food made using craftsmen skills outside of the industrial food and transport systems will be slow food. They have set an example for us to follow. All of us with an environmental perspective on the world should be thinking hard about our relationship to time and how we might apply the same principles of conservation, use reduction and alternative approaches that we have come to take for granted with other finite resources. I hope the Sustaining Time project will help us with that thought process. |

Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed