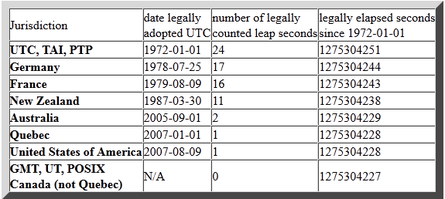

Testing an atomic clock (Jessamyn (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) Testing an atomic clock (Jessamyn (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) Originally published on the Time of Encounter blog, part of an AHRC funded project exploring social aspects of time. So in my last post I suggested that clocks are not devices for measuring the time, but are instead tools for coordinating ourselves with what is significant to us. This kind of claim chimes strangely with our usual understanding of the clock. Within philosophy and social theory, for example, ‘clock-time’ is the antithesis of lived, subjective ‘temporality’. Far from being about significance, value and choice, clock-time is regularly understood as an objective, quantitative measure of the flow of an all-encompassing time. This division between objective time and a human or lived ‘temporality’, is neatly described by David Couzens Hoy who suggests that while time “can be used to refer to universal time, clock time, or objective time”, temporality “is time insofar as it manifests itself in human existence” (xiii). For philosophy then, clock-time is not about the human, not about death, politics, duration, seasons, cycles or the backwards-forwards movements of memory and hope. Within social theory too clock time is often understood as being divorced from the time of social life. Instead clock-time is that which separates us from the variable rhythms of our lives and supports our insertion into an unrelenting globalised capitalism. As Barbara Adam puts it: Clock-time, which was developed in Europe during the 14th century, no longer tracks and synthesizes time of the natural and social environment but produces instead a time that is independent from those processes: clock-time is applicable anywhere, any time. Context no longer plays a role (123) But is this really the case? Is clock-time really context free? What I want to suggest is that if you look a little more closely at the clock and how it works, a vertiable cavern opens up below you and instead of a linear, dependable, unending time, you actually find that at the heart of quantitative time itself there are multiple political battles about context, significance and value taking place. I’ll give just a few examples here and will be discussing more in later posts. To begin with, there is no such thing as clock-time in the singular. Instead what we normally call clock-time is in fact the product of the negotiation between two different times, International Atomic Time (TAI) and Universal Time (UT1). Atomic time is told in reference to the ceasium atom. Universal Time, on the other hand, is told in reference to the rotation of the Earth. Importantly, these two times do not synchronise with each other, since the Earth’s rotation is variable. It slows down and speeds up, and so in order to remain synchronised with cycles of night and day Universal Time often needs to be adjusted. So while atomic time would seem to provide the precise, regulated time philosophers and social theorists often refer to when they mention clocktime, we do not actually use TAI itself to tell the time. If we did we would become desynchronised with the rotation of the Earth. Instead our clock time (or civil time) is actually a third time known as Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). This time is produced by adding leap seconds to International Atomic Time in order to stay synchronised with Universal Time.  To make it more complicated, different countries adopted UTC at different times and so have legally recognised different numbers of leap seconds. As you can see from the screen shot below, from a website that tracks these differences, in Germany 16 more seconds have legally elapsed than in the U.S. And one province in Canada, Quebec, is one legal second ahead of all the other provinces in the same country. The complicated and contradictory world of time keeping is even further illustrated in this fascinating look at the social and political character of time zones from the BBC. What this all means is that our clocks are not universal and neither are they context-free. Instead they are regularly adjusted in recognition that our desire for objective precision must nonetheless be tempered by the fact that our lives are spent on an unsteadily spinning globe. Interestingly, there are currently debates raging over whether to do away with leap seconds altogether. This is because their unpredictability (they are added irregularly, with six months notice) makes them problematic for systems that use precise time-keeping such as navigational systems, financial systems and the internet. Even still, this debate is not one over how to make the clock free of context, but needs to be read as a process of making choices about what is more important for us to stay coordinated with. We may well end up deciding that staying coordinated with the systems that support our current economic, transportation and communications infrastructures is more significant to us than staying coordinated with the Earth itself. But this is still a choice over what sets of relations and what kinds of communities we value, a choice over which temporal rhythms we think it necessary to stay in touch with, and which we think we can afford to ignore. Michelle Bastian References: Adam, Barbara (2006). “Time.” Theory, Culture and Society 23(2): 119-126. Hoy, David Couzens (2009). The Time of Our Lives: A Critical History of Temporality. Cambridge, Massachusetts, MIT Press. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed