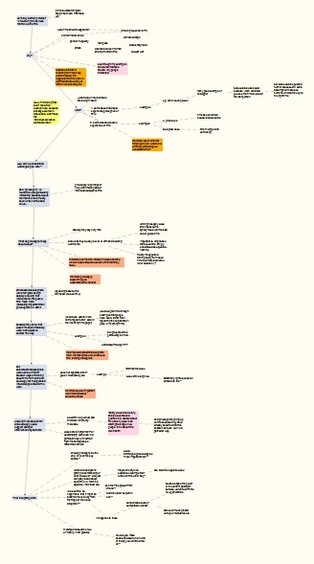

My first article outline since high school! My first article outline since high school! Over the past few years I’ve been lucky enough to be involved in quite a few different funded projects. I’ve been exploring clocks, local food, more-than-human participation, transition towns and more. Now that most of these have come to an end, I’ve got more time to focus on writing up the results of these projects and sharing them more widely. I had been looking forward to this part of the research process, but as soon as it arrived the familiar anxieties around writing came flooding back. So just before Christmas I thought it might be worth reviewing my writing process to see whether I could incorporate any new methods. I’d done a lot of this while I was writing up my Ph.D. (two of my favourites here and here) and this had helped me get a lot more writing done. But I still thought of writing as a painful process where every word was written in blood. When I came across Robert Boice’s claim in Professors as Writers that writing could be painless, and even enjoyable, it seemed like a dream. But recently I put some of his ideas into practice and was astonished to find myself writing a 5,000 word paper over three days, while also doing a course from 9-5 each day. Most of the time the writing was pretty painless and as I went along I even started to enjoy it. So I thought I’d share some of what I tried and why it seems to make such a difference. What stood out for me in Boice’s guide is the way he brings spontaneous writing together with the outlining and structuring process. He suggests that when starting a piece of writing, first spend between ten minutes and an hour writing about your topic. Don't worry about structure or getting anything perfect. Just write. The main aim is to get your ideas down on paper. Once you’ve done this, review what you’ve written and make a note of the key points, clustering them around a few main themes. You can then sort out these clusters into a logical structure that will then serve as an initial outline for your next draft. Repeat this process for each of the sections you’ve highlighted in your outline until you have your first full rough draft. Usually when write I sit staring at the same few sentences, trying to work out the right way to begin. Often I furiously delete them when I realise that they won’t flow into what I need to write next. But using spontaneous writing I could set aside all those anxieties about getting things in the right order and just write everything down. I trusted that I would go back through it all later and sort it out them. It felt lovely to be able to delegate that task to my future self and just get on with getting my ideas out on paper. This spontaneous writing tended to be quite conversational at first. I wrote about how I was feeling and what other things I was worrying about, before getting down to the specific topic at hand. This meant that I wrote a lot more than I needed. For example, I wrote 1200 words for an introductory paragraph that ended up being 300. But even with this ‘wastage’ I still wrote the whole thing more quickly and easily than I ever had before. I wondered whether this self talk was a necessary part of getting into the swing of things. Perhaps a bit like the way people usually spend some time chatting before getting to the main reason for their meeting. Maybe I need to observe these social niceties even with myself. Going onto the next stage of outlining was pretty much a revelation. I hadn't ever used an outline in the past, apart from when I was forced to in high school. It didn’t make sense to me to outline when I needed to write to figure out what I wanted to say. But using Boice’s method (and my new favourite programme Scapple) I ended up with a nice clear outline for the whole paper and a good sense of where each section was headed. I was surprised at how complicated the outline was. The implication was that in every previous piece of writing, I’d been doing this hard work of figuring out the structure of my paper at the same time as writing the first draft. No wonder I had always found writing so painful. During my Ph.D. I got much more used to the idea that writing was a craft, rather than an innate ability bestowed on the few. I believed I could learn to be more disciplined or have better technical skills. But what this process showed me was that I hadn’t extended the idea of writing-as-craft to the possibility that you could also learn to write in a way that was enjoyable and relatively anxiety-free. I'm not there yet, but a least now it seems a little less like a dream and more like something I might come to learn. Originally published on the Sustaining Time blog, part of an AHRC funded project which asks the question: What would be the time of a sustainable economy?  Economics by Mark Wainwright (CC BY 2.0) Economics by Mark Wainwright (CC BY 2.0) It’s been a little while now since we’ve put up a new post on this project and I can’t help but feel the irony of not having enough time to devote to a project that is exploring the possibility of developing more sustainable relationships to time. But as perhaps many others have found, your projects never really forget about you. They keep calling to you, cutting through all your busyness and eventually reeling you back in. So to get back into the swing of things, I wanted to revisit some of the core questions that first inspired the project. Starting off with the most obvious perhaps: Why might a focus on time be important for understanding how to shift to more sustainable economies? The perfect storm of multiple crises, including climate change, the peaking in supply of a whole range of key resources, as well as the astounding inequality fostered by current economic systems, have turned many towards developing and implementing alternative approaches. Challenging the philosophical basis of conventional economic theories has been an explicit aspect of this. As a result, the dominant paradigms of neoclassical economics are, at best, seen as being comprised of naive assumptions that fail to capture the complexity of human interdependencies on each other and on the environment. All around us, the dominant stories of how people interact with each other and the kinds of incentives and rewards they respond to are shifting. Instead of competitive self-interested units, we are more generous, more co-operative and more complex than main-stream economists give us credit for. The structure and characteristics of the web woven between the human and non-human, between the biological, the mineral and the elemental are being questioned and described in new ways. Gift-based economies, the new commons, cooperation, abundance instead of scarcity and distributed networks are just a few examples.  Bestwood factory entrance by Sludge G (CC BY-SA 2.0) Bestwood factory entrance by Sludge G (CC BY-SA 2.0) How might time fit into this then? If time is just an objective flow that we measure, then it has about as much to do with economics as π (pi) does. It’s an unchangeable constant that we just need to live with. But what if this story about time is as much of a distortion as the story about ‘economic man’? What if time is also more complex, more interconnected and more dependent on social webs than we’re usually taught? That like the maps that tell us stories about space, our clocks are not simply telling us ‘the time’ but are telling stories about time that are cultural, political and partial? What if time is tied to our webs of relations in such a way that when these webs change so does time? There is already research that suggests that broadly speaking different economic systems seem to be associated with different approaches to time. For example, pre-industrial societies with task oriented time, industrial capitalism with an intensification of clock-time and late capitalism with speed and acceleration. And if we look for further clues within alternative economics, new sustainable times come tantalisingly into view. Steady-state futures or degrowth displace stories of the progressive arrow of time. Movements like Slow Food, Permaculture or Transition are making deliberate attempts to redesign everyday life around slower tempos and complexity-based models of social change. This suggests that social change doesn’t only happen in time, but happens through changes to time itself. The aim of this project then is try see if we can make some of these shifts in time more visible and more intelligible. But in going about this, we are making the following assumptions which make things more complicated:

|

Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed